[Cover Photo: Steve Darby. Licensed under Creative Commons 2.0.]

By Sarah Pfohl

The following text is from an invited talk shared at ‘Currents’, the 2022 Midwest Society for Photographic Education (MWSPE) Regional Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio, USA on Friday, October 7, 2022.

Welcome, folks. Thanks very much for being here this afternoon and to the conference organizers for creating space for these ideas and the artistic and pedagogical work I’m making inspired by ideas about ability, legibility, and representation.

I’m a proudly dis/abled, chronically ill artist and teacher and about 15 years ago, as a graduate student studying education, I came into contact with ideas from disability liberation that completely turned inside out my thinking about myself as a sick person. Over time, these ideas have become foundational to me as both an artist and a teacher. I’ll share a few of those ideas with you, offer some ways you might bring them into your own work with people (in teaching or beyond), if you don’t already, and then talk about the photographic work I’ve been making inspired by the anti-ableist movement that is disability liberation. I’ll move in a couple different directions — teaching, theory, identity, artistic work. In my body-mind, life, and work, it’s all intertwined.

A few final contextualizing notes by way of introduction:

First, notes on language. In this talk, I’ll refer to ableism, which is oppression based on real or perceived aspects of a person or group’s ability. The language I’ll use throughout this talk is specific and intentional, it may sometimes meet you as surprising. Next, I’ll draw ideas from lots of different arenas of thinking and action including disability studies, disability rights, and disability justice. This talk will provide a really quick, condensed introduction to a few pieces of a huge, rich terrain. I’m skating across the surface, please check out the resource guide for more information, if you’re so inclined, or reach out, I’m happy to chat further.

I’m one person among so many within the disability community. Data estimate 1 in 4 U.S. adults under the of 65 manages a diagnosis. In other words, the disability community is huge, there are almost certainly disabled people in your midst, whether you realize it or not. The community encompasses billions of people worldwide. I’ll speak here through the lens of my own experiences and on behalf of myself, not on behalf of an entire group of incredibly diverse of people.

Finally, a ‘why should you care’ note. Taken as a whole, the concepts I offer here mean to invite, increase, and normalize meaningful participation in our world from a huge group of individuals positioned as less than, a huge group of individuals whose separation from the non-disabled world is deeply rationalized, dominantly framed as humane, and in many cases currently legal. Disabled people deserve humane treatment, full participation, and have incredibly valuable perspectives and knowledge to contribute to our world.

Anti-ableist teaching strategies

First, I’ll cover three concepts in contemporary disability liberation that might be of use in teaching and learning contexts and beyond. I’ll define each one, or, in one case, paired set, and then talk a little bit about practical implications.

I’ll talk first about the intertwined concepts of the medical model of disability and the social model of disability.

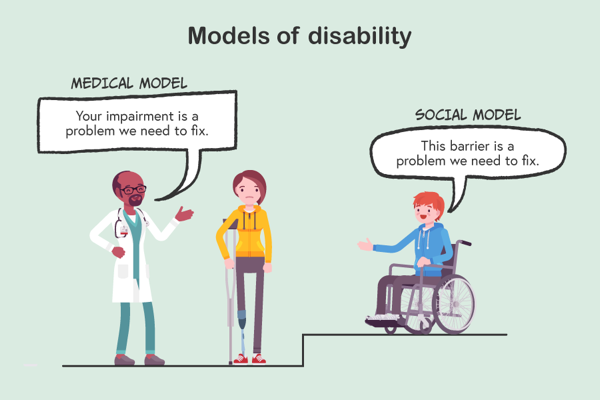

The medical model and social model construct disability in 2 diametrically opposed ways, in particular they locate the origins of disability in 2 very different places. Taken together, the medical and social models can point toward ways in which contexts disable people.

Image source: FutureLearn (n. d.). Models of Disability. [cartoon]. Inclusive Education: Essential Knowledge for Success – Queensland University of Technology. https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/inclusive-education

Accessed via https://inclusiveeducation123.wordpress.com/2020/03/30/breaking-barriers/ on September 15, 2022.

The image above embodies one traditional way of introducing the medical and social models. We see in the center of the image a frowning person using a mobility assistive device (the crutch) and a prosthetic next to a step. On the left-hand side of the image, a medical professional says, “Your impairment is a problem we need to fix.” This speech bubble is labeled as ‘medical model’ On the right-hand side of the image a person using a wheelchair says in reference to the step, “This barrier is a problem we need to fix.” The speech bubble there is labeled as ‘social model’. A few things I want to activate your attention toward in this little cartoon:

Within the medical model perspective, we see disability defined as an impairement—through this it is referred to in deficit-centric, negative terms. This positioning of disability as a limitation, a disorder, a disadvantage is a key characteristic of the medical model. Additionally in the medical model perspective, disability is defined as a condition rooted within an individual, it’s a problem, located first and foremost within a person. By extension, the diagnosed person becomes the problem, especially if they can’t be “fixed”.

The social model perspective provides a counterpoint arguing that disability is not always and only located within the individual, rather it is socially agreed upon and produced out of the interaction between people and the world around them. Within the context of the social model of disability, inflexible, rigid, beliefs, attitudes, and physical structures produce what we call disability through the pathological unwillingness of those forces to shift or change such that they may accommodate a wider range of human diversity.

The social model doesn’t position the disabled person as a problem or as in need of fixing. Rather, it provides a perspective that normalizes human difference as a fact of human life, rather than pathologizing certain ways of being in favor of upholding existing, oftentimes-ableist social norms.

In dominant culture the medical model is normative, you probably have extensive experience with it just by being alive in the world, while the social model of disability reframes thinking and conversations about ability fundamentally. For the purposes of teaching, the paired models provide a number of possibly useful implications:

Remember that there are a growing number of disabled people who view disability as a part of their identity that connects them to a rich, important, diverse culture with an exciting history and future. Disability pride is a real thing.

Expect diversity in conceptualizing your teaching. Folks interested in realizing more ability-inclusive teaching moves might check out the Universal Design for Learning framework for suggestions. UDL encourages educators to provide multiple pathways into content engagement alongside multiple means of content representation and learning expression. Within a teaching context, flexibility can be a powerful anti-ableist teaching move.

Be thoughtful about the elements of your teaching practice designed to socialize students into an existing normative framework. If you are socializing students toward something, what is the lineage behind that something? I bring this up because when I’ve led PD on these topics previously, one of the most common pieces of push back I get is — but it’s my job to socialize my students even if that’s ability exclusive. Some teachers resist the social model lens because part of their mission is conforming their students into productivity relative to the existing social order. You might be mindful of this, as it can be ability-exclusive given the intense ableism present in our existing social order.

A few critical notes here:

The social model of disability, when present in public discourse, is poorly understood and often completely misconstrued. I strongly encourage you not to Google it, because the results bear little relation to the actuality of the concept. Check out the Rethinking Disability book I cite on the resource guide (see below for guide) for reliable information if you want to learn more.

The social model doesn’t argue against medical intervention. It is not saying that one should stop going to the doctor or that medical support is a bad thing. It does argue that disability-related expertise can be located in many places, within and beyond medical practitioners.

Finally, the social model doesn’t argue that disabled people must embrace, love, be happy about being disabled. It does challenge the idea that disability is always and only a negative thing, but doesn’t prescribe the feelings disabled people “should” have about themselves.

I’ll close this section with 2 quotes from disability liberation heroes that underscore the value of shifts in thinking connected to the social model construction of disability (both quotes pulled from this NYTimes article).

The first is from disability rights activist Judy Heumann: “The way society thinks about disability needs to evolve, as too many people view disability as something to loathe or fear. By changing that mentality, by recognizing how disabled people enrich our communities, we can all be empowered to make sure disabled people are included.”

The second is from disability justice activist, writer, author, and founder and director of the Disability Visibility Project, Alice Wong: “We [disabled people] should not have to assimilate to a standard of “normal” to gain acceptance.”

The next concept I wanted to bring into the room is much narrower in scope—I wanted to talk about presuming competence as a mindset and lens. I first encountered this concept in Kathleen Collins’ great book Ability Profiling and School Failure: One Child’s Struggle to Be Seen as Competent.

The simple yet revolutionary argument embedded within presuming competence is that disabled people have capacity. Disabled people are often always and only framed around what they can’t do, especially educationally, and the list of can’t dos becomes the center column of that individual’s identity for others. We see this happen educationally especially when the terms of someone’s accommodation rub up against the teaching norms already in place in a particular instructor’s teaching and learning context/teaching practice. Years ago, I worked with an art history professor who very emphatically didn’t allow students to have screens of any kind in their classes but received, during the first week of school, an accommodation letter from a student indicating that they required the use of a laptop for note-taking during class meetings. Of course, an ADA accommodation is a legally-binding document and violating the terms of an accommodation is a violation of the student’s federally-mandated civil rights under the ADA. The student became “the student who can’t write their own notes by hand” and instead of finding a creative solution the professor pushed the student out of the class. They told the student to either stop using the screen or sit in the back of the classroom so that they didn’t “distract” their peers with the screen. The student dropped the class in response.

Disabled people can do a lot of things! We carry so much capacity. Finding creative ways to align existing circumstances with an individual’s existing capacities to in turn promote more full participation can produce more ability-based inclusion for all. An argument for teaching from disability liberation is to keep the learning goals the same, but increase the pathways toward them. A couple years ago I worked with a sculpture professor who had a project that included chop saw use. He knew several incoming students would not be able to use the chop saw as it was installed in the wood shop. In conversation, it turned out that the primary project learning goal was centered around creating a modular object, so in that particular case increasing the number of materials with which students could work, allowing students to work with both wood and paper, increased accessibility while maintaining the project objectives.

The last concept that I want to talk about is language associated with disability. Here the literature has a couple different suggestions. The first suggestion has to do with ability-related identifiers people use. Here’s a list of preferred ability-identifiers of some of my friends:

disabled, dis/abled, Disabled, sick, crip, Mad, neurodivergent, chronically ill, ability non-normative, disabled person, person with a disability, physically ill, mentally ill, Sick

Which ones are right? There are no monolithically correct identifiers that I know of at this time.

Don’t most of these words mean the same thing? No, they don’t. Disability as an identity and cultural category is incredibly diverse, one person’s relationship to a particular identifier may be totally different than another person’s relationship to the same word.

Here’s what I can offer: People’s identifiers are highly specific and personal, use the language offered by individuals as they offer it. In the same way that you wouldn’t correct a student on the spelling of their name or pronoun use, don’t correct someone’s ability-related identifiers—accept what they tell you. Different identifiers do connect to different movements and spheres of thinking within disability liberation. Assume people use the language with which they identify themselves intentionally and honor it. SLIDE

In my own case, I use dis/abled and chronically ill. I use the word disabled to name the social conditions under which I live my life. What I mean by that is that I live in a world that constantly, tens of times each day, reminds me that I don’t belong here and I should normalize or get out because the diversity I embody isn’t important.

I write dis/abled with a back slash between dis and abled to connect myself back explicitly back to disability studies. Dis/abled is how some folks in disability studies write disabled to underscore the socially constructed nature of disability at a formal, linguistic level and that resonates for me, so I use it. Disability studies is also where I first encountered ideas that fundamentally reframed my thinking about ability and illness, so my use of a term anchored there as an identifier does honor to others’ works and points toward my affiliations.

I say ‘chronically ill’ to hold up and foreground my biological reality as a person engaged in the constant labor and care associated with managing multiple, incurable diagnoses.

And all of these will grow and change as the movement grows and changes, which is a beautiful thing.

Second, relative to disability-related language I wanted to be sure to identify the distinction between person-first and identity-first language. Many folks have heard of person-first language as it pertains to ability. To summarize, the idea is that one says ‘individual with a disability’ or ‘person with [insert diagnosis]’ foregrounding the person first and ability status second, rather than the inverse—foregrounding the ability status first and the person second. Folks who prescribe to person-first linguistic patterns argue that by naming first the individual, the individual becomes less defined by their ability status.

Identity-first language turns that around and argues that linguistically foregrounding ability-related identity by saying ‘disabled person’ promotes disability pride and de-stigmatizes oftentimes-negative preconceptions of the word disabled. Some proponents of identity-first language also argue that in using that language pattern they name disabled people’s life experiences as they more truly are—an ableist world reminds disabled people that they do not belong. A common argument against person-first language from a disabled person is, “I’ll use person-first language when I start getting treated like a person.” As you may have noticed, I’m using identity-first language throughout this presentation.

For a long time person-first language (person with a disability) was far more common and that linguistic norm is very present in many fields, especially medical and educational spheres. It isn’t a bad approach, especially if you’re non-disabled and talking about disability or you find yourself in the position of having to choose one or the other. In those moments, person-first works great.

However, if you encounter someone, like a student, who is disabled and uses identity-first language honor that. Again, use the identifiers someone supplies you and assume identifiers used are used intentionally. Resist the urge to teach a disabled person who identifies as a disabled person about person-first language.

The final perspective from the intersections between language and ability I wanted to offer into this space is an invitation to use and model anti-ableist language.

Ableist slurs are quite common and often used unintentionally. They might emerge as language patterns that position a diagnosis category or way of being in general in a negative light or from a deficit standpoint. A few examples and how they would be corrected:

I was engaged in a blind struggle to move forward. — I was engaged in a careless struggle to move forward.

He’s stuck in a wheelchair. — He uses a wheelchair.

That’s a lame excuse. — That’s an inadequate excuse.

It seems subtle, but it’s a big deal. I find that more and more of my students know this content and read the world around them, looking for mentors and allyship, informed by the subtle hints provided by the gatekeepers in their lives. Lots of disabled young people in higher education don’t and won’t disclose but need help and actively decreasing ableist slur use helps vulnerable students find folks who can provide critical support. Again, the tip of a huge iceberg but a brief outline of ideas I’ve come into contact with that have been useful to me as a teacher.

As I mentioned, statistically 1 in 4 U.S. adults under the age of 65 fall into the category of disabled. Which would mean, if, for example, you’re a teacher in higher education, that in a class of 20 students you should statistically receive 5 accommodation letters. Of course, there are many reasons people don’t self-identify formally through disability services. I share these numbers to underscore that ability-related non-normativity may be far more present in the spaces within which you move than you realize. These ideas, aimed at promoting the humanity and humane treatment of people historically treated terribly (Google ‘Willowbrook’ for more information) can have a big impact even if you think they might not pertain to you.

Imaging what’s wrong with me

I’ll shift now to the artistic work I’ve been making precipitated by the ideas I just shared and start with some facts about my body.

The primary biological diagnosis with which I was born is currently called osteogenesis imperfecta, abbreviated as OI. As a diagnosis category, OI is characterized by the OI Foundation, the primary US-based advocacy body associated with it, as “complicated, variable, and rare” in appearance. Statistically, worldwide, around 1 in every 15,000-20,000 people lives with osteogenesis imperfecta. Within the context of my own life, I’ve never knowingly met in person someone else with OI.

With OI, which is incurable, I have less of a particular protein in my body than deemed medically normal and within that, the smaller amount of that protein I do have is designated, in medical terms, as “qualitatively abnormal”, which is one of the many fun things I get to hear medical professionals I’ve just met call me—“qualitatively abnormal”.

More specifically, parts of my body—my bones, heart, lungs, eyes, and ears—work differently than most other people’s. My bones break, sometimes for little or no discernible reason. I’ve broken bones in my legs, arms, hands, feet, fingers, and toes, I’ve fractured my pelvis, my skull, and both clavicles. I can have trouble with the mechanics of my body, my ability to walk ebbs and flows.

I also manage now OI’s offshoots and degenerative progressions, as a diagnosis it proliferates over time. I manage Deaf gain (referred to as hearing loss in hearing culture), early-onset osteoporosis, anxiety, depression. So that’s a brief description of the nature of my body-mind from a medicalized, biological, diagnosis-label perspective.

I share this not in an attempt to evoke sympathy or pity, but to outline what counts as normal within the context of my own experience. As a site, my body requires constant management and care. I share information also to cure any deniers—I don’t usually read as disabled and chronically ill, it’s common for people to question me on that, so specifics and disclosing can help build my credibly.

As a dis/abled, chronically ill artist coming into contact with ideas from disability liberation, I started to wonder what implications they might have for my artistic work. As I worked to shift my consciousness away from medical model thinking and toward social model interpretations of the world around me, I began to notice and become more critical of the negative representational tropes associated with illness and disability that permeated the world around me. Experiences of disability are incredibly diverse but, due to ableism, the visual language commonly associated with disability was narrow and unimaginative.

As I started to photograph toward my own representation of disability, I wanted to visually push back against these norms. A question I started to chew on often was, “Can I make a representation of disability that feels true to my lived experience, that doesn’t include the body, and that goes beyond the common, deficit-centric narrative?”

I looked around for some inspiration. I started to notice also that the representations of disability that presented the most complex, nuanced portraits of diagnosis management and ability non-normative life were first-person. By ‘first-person’ I mean they were crafted by an individual with first-hand experience of diagnosis management. I had been reading within the field of disability life writing, an approach to writing that argues for the value of diverse narratives about disability written by disabled people, and started to look for examples of disability life photography.

Through the lens of the social model of disability, a disabled person is positioned as the primary expert on their own life and body-mind. A disabled person is, through the social model lens, a knowledgeable authority on what it is to be sick. This social model perspective overturns dominant medical model thinking which locates disability-related expertise in basically anyone expect the disabled individual. For example, it’s quite common for a medical professional’s perspective on an illness they have never experienced to be held in higher regard than the perspective of an individual in medical care literally experiencing that particular illness; an insidious norm that extends historical positioning of the disabled person as helpless and wholly reliant when in reality, of course, the person who knows the most about a particular body is the one living within it.

Within photography, I came into contact with work by artists like Jaklin Romine, Megan Bent, Sara J. Winston, and Frances Bukovsky. I gained so much inspiration from this work, and it really gave me the steam and permission I needed to believe first-person ability-related representations were both critical and far more rare than ideal.

With a bit of visual footing, I moved forward. As a diagnosis management strategy, I am prescribed daily walks. I walk often in a forested, public park near my home in Indianapolis and I began to take my camera with me and photograph botanical forms during my walk.

I work very intuitively and started to photograph in the forest without any particular ambition for the images in mind. Strategically, I did want to photograph while walking to combine two necessary tasks in my life—these prescribed walks, as required by my doctor, and producing artistic work, as required by my job and spirit.

Being disabled and chronically ill, my time is structured toward preserving my life in a very specific, calculated way. I spend a lot of time on diagnosis management and care each day, stewarding my body, and then far more time dealing with the MIC, the medical industrial complex—spending my precious time engaged in tasks like the following: on the phone with healthcare providers, driving to appointments, engaged in appointments, on the phone with co-pay programs and my health insurance, trying to recover emotionally from the ups and downs of medical news and receiving surprise medical bills to the tune of thousands of dollars.

Folding diagnosis management and making together, pairing 2 things I had to do, helped me feel more in control of my time and body. I also wanted to take a demand from and limitation of my diagnosed body, it’s need for these walks, and reframe it as a generative space by building photographing into the ritual practice of care rooted in these walks.

As I reviewed the work I made in the park, I found myself most drawn to the blurry, indistinct backgrounds in the images and I began to lean into that. Again and again, as I looked through the photographs, paying closer attention to the blurred out components over the sharp ones the phrase, “That looks like me.” popped unbidden into my mind. Over time, the phrase grew into a conviction and I’ve found that for me, one of the most important parts of growing into an artist has been learning to take seriously and interrogate the weird, unexplainable truths my body-mind unbidden offers.

As I investigated my identification with blurry botanical forms, I realized my photographs contained visual continuities with the medical imagining I encountered in my daily life. They looked like microscopic versions of medical evidence related to my diagnoses.

They looked like x-ray enlargements, the thready-ness of bone, the haziness of tissue.

Over the course of my life as a multiply-diagnosed person I have likely been medically- and diagnostically-imaged more than I have been photographed for memory’s sake. Put another way, I think there are probably more representations of me in the form of diagnostic evidence like x-rays than there are pictures of me traveling, with friends, at parties, etc. This isn’t to say I don’t go out, it is to underline that my experience as patient in medical settings is extensive and life-long.

I found tremendous power in creating my own weird version of diagnostic-ish imagery. I can’t underline that enough. After years as subject to medicalized imaging practices, for the first time I was the person making the x-ray, taking the scan, in effect pressing the shutter release from within my radiation-protected bubble rather than the individual lying prone and covered with lead on a cold plastic table while a device circled my body as it emitted a series of beeps.

Osteogenesis imperfecta model no. 45

Visually, I think of the work as messy, a resolved but wild tangle that flickers between clarity and ambiguity. Born into a body that carries multiple non-visible diagnoses, my external appearance and my internal reality rarely coincide, especially within the world of the general public imagination. In other words, I don’t look like one of the most foundational aspects of who and what I am, I pass for fine but am pretty sick, and that tends to trip people up. I continued to think into that phrase, “That looks like me.” and realized the flora I trained my lens toward and then intentionally rendered out through the camera as disorienting, messy thickets punctuated by moments of clarity aligned with the illegibility foundational to my lived experience of non-visible illness.

On one hand, I can say my visible appearance misdirects, a symbol for lived experiences I have never known and will never know. My external body feels like a costume that doesn’t fit or a deception. On the other hand, common ideas of what disability looks like bear very little relationship to the hugely diverse ways in which disability actually presents. Though this, I become clear in flashes.

Osteogenesis imperfecta model no. 97

Being read and socially positioned as non-disabled is, of course, at times a privilege but in some circumstances can be incredibly dangerous. My life has been put in danger many times because people assumed I wasn’t sick and ascribed abilities to me I didn’t have or expected performance from me I could not provide. In these moments of illegibility my choice is disclosure or danger.

Additionally, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve disclosed in an attempt to pull myself out of danger but have been denied (literally told things like “That’s not possible.”, “No, you don’t.”) because I don’t live up to someone else’s version of what a disabled person looks like. It’s this strange struggle to be seen and I found image-making processes that I could use to render visually these feelings. The anti-ableist teaching implications here are to two-fold: 1) trust what people tell you about their circumstances, even if they don’t/can’t provide medical documentation, 2) don’t forget that interior and exterior circumstances don’t always align

Osteogenesis imperfecta model no. 76

I started to think of the work as my body without my body, as non-traditional self-portraits. A piece of useful context here is that I grew up in rural New York, 2 miles outside of a village of about 650 people. I spent my first 18 years surrounded by far more plants and trees than people and, this isn’t a joke, my first best friends were the wild grasses and greenery around my parents’ house. That, within the context of this particular body of work, I’ve located botanical forms as a stand-in for my innermost physical realities and psychological experiences aligns with the deep flora connections I witnessed and cultivated within the rural culture I know best.

I don’t prescribe to the medical model idea of disability as a monolithically bad thing. Like many folks in the disability liberation community, I wouldn’t take a cure were I offered one, and I locate some of the aspects of my personality that have become the most valuable to me as originating in and inseparable from my lived experiences as a disabled person. My incurable body is my superpower and in spite of powerful, oftentimes-eugenic societal messages to the contrary it has never served me to believe I’m less-than, that there’s something “wrong with me” because of the diagnoses I manage. I wanted to make a representation of disability that contained moments of beauty to honor the power and value of disability as I know it.

Osteogenesis imperfecta model no. 5

The last framing note I’ll share relative to this on-going work—many disabled, chronically ill people maintain a dossier of critical medical information. This dossier might include hundreds of pages of content like care information and instructions, health insurance documents (if one has health insurance), diagnoses, or emergency information. My dossier is a 3-inch, blue, 3-ring binder that I take with me to medical facilities to prove myself and direct my care, especially in emergency situations. Because the primary diagnosis I manage is rare and medical professionals are taught that common diagnoses are common (when you hear hooves think horses, not zebras) I often have to tell the people taking care of me what to do. Sometimes, I am the first person with OI a medical professional I’m working with has ever met in person.

Osteogenesis imperfecta model no. 55

Taken together the images in this ongoing project operate as a slant dossier. They are my models of my lived experiences of rare, non-visible diagnoses. They are evidence of my internal genetic reality as I imagine it models of my social experiences of sickness in a deeply ableist world. Sometimes I wonder what would happen it I could take my pictures to a medical professional and be like, “Here, this is my version of what’s wrong with me. Diagnosis this.” Finally, I will just mention quickly, my idea right now is for the project to include, in its final form, 206 individual images, one for each bone in most adult human bodies.

Sarah Pfohl is a dis/abled, chronically ill artist and teacher, currently serving as Assistant Professor of Photography and Art Education Coordinator in the Department of Art & Design at the University of Indianapolis. You can read more about her and her work here.

Resource guide

Some very good books:

Rethinking disability: A disability studies approach to inclusive practices, Jan W. Valle and David J. Connor, 2019 (2nd ed.), Routledge (disability studies)

Any text by Eli Clare. A great starting point: Brilliant imperfection: Grappling with cure, Eli Clare, 2017, Duke University Press (disability justice)

Being Heumann: An unrepentant memoir of a disability rights activist, Judith Heumann with Kristen Joiner, 2021, Beacon Press (disability rights)

Disability visibility: First-person stories from the twenty-first century, Alice Wong (Ed.), 2020, Knopf Doubleday (disability justice)

Academic ableism: Disability and higher education, Jay Timothy Dolmage, 2017, University of Michigan Press (disability studies)

Ability profiling and school failure: One child’s struggle to be seen as competent, Kathleen M. Collins, 2012 (2nd ed.), Routledge (disability studies)

Disability and difference in global contexts: Enabling a transformative body politic, Nirmala Erevelles, 2011, Palgrave Macmillian

What can a body do? How we meet the built world, Sara Hendren, 2020, Riverhead Books

Academic journal articles:

Collins, K. & Ferri, B. (2016). Literacy education and disability studies:

Reenvisioning struggling students. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,

60(1), 7-12.

Ferri, B. A. & Connor, D. J. (2005). Tools of exclusion: Race, disability, and

(re)segregated education. Teachers College Record, 107(3), 453-74.

Netflix: Special, Crip Camp

YouTube:

Mia Mingus, opening keynote, 2018 Disability Intersectionality Summit

Substack:

CripNews by Kevin Gotkin

Instructional strategy: