[Photo by hxyume via Getty Images]

By Ann Larson

Republished from Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

I was managing the front end of a grocery store one night during the height of the pandemic when a man with a bulge under his long black coat strolled through an empty checkout lane. One of the dozens of unhoused people who lived in encampments blocks from the store, the man walked past me with such confidence that I wondered if he really didn’t know what was about to happen.

The radio buzzed in my ear. “Let me know when that guy gets to the front,” said a security guard, “I’ll call John.” Another employee had seen the man slip something into his coat, and security was already watching him. “He’s headed to the exit,” I replied.

John appeared and cut the thief off at the door while another employee, built like a linebacker, approached from behind. The shoplifter tried to run, but John grabbed him and shoved him hard against the dry ice cooler. Groceries dropped to the floor. The man screamed and tried to break free, shouting, “Get away from me!”

John wrestled the shoplifter down, smashing his face sideways against the concrete. The other employee tried to tie the writhing man’s hands with a zip tie. John shoved a taser into the thief’s back, and tased him until he stopped moving. They dragged him away.

A bagger gathered the groceries scattered on the floor. “Donuts and milk,” he said, as he tossed the products on a checkstand. The donut box was crushed, and the milk carton was leaking. The store couldn’t sell those items now.

Minutes later, John radioed to report that the cops were on their way. As we had done numerous times before, my colleagues and I watched as a thief was escorted out of the store in handcuffs.

Stores Under Siege?

I began working at the store a few months before the tasing incident and just as the media had begun to report on a spike in retail crime. Stories about stores under siege were common last summer and fall. The more sensational entries described empty shelves and “third world” conditions at outlets targeted by thieves. The media’s focus both reflected and stoked broader fears about public safety. A national survey showed that almost three-quarters of Americans listed crime as a top concern.

I was skeptical about the reports. Evidence cast doubt on the claim that shoplifting was on the rise. Property crime had fallen during the pandemic, and data from the National Retail Federation showed only a slight increase in stores’ product loss during the same period. Some argued that the real issue was the increased visibility of theft thanks to smartphones.

I also suspected that the media’s focus on retail crime was part of a conservative backlash against criminal justice reforms. In the Atlantic, Amanda Mull suggested that the “great shoplifting freakout” was an attack on progressive states and cities that had reduced penalties for some offenses. Others accused the media of pushing pro-police propaganda during a time when theft was actually on the decline. The political motivations of anti-reformers were especially clear in California, where District Attorney Chesa Boudin would lose his job due to a recall campaign funded by billionaires and real estate interests in a city one media outlet called a “shoplifter’s paradise.”

There was no doubt plenty of truth to the progressive position that the retail crime wave was mostly media hype. But as I continued in my new job, my views grew somewhat more complicated. There really were a lot of shoplifting incidents at the store where I worked. I had no idea if they were more common than before the pandemic, but I knew that they were disturbing for workers and disastrous for shoplifters, who were sometimes met with violence and often with criminal penalties. Regardless of whether the spike in incidents was real or imagined, I began to see shoplifting as a genuine problem — not because of the stolen merchandise, but because it often kicks off an escalating chain of events that are damaging for everyone involved.

Guilt at my role in the tasing incident pushed me to ask a basic question: What historical conditions had put me and others in that situation? The answer revealed that what we think about shoplifting is the product of propaganda — a much deeper and more foundational story than the one being called out by some progressives. The way our society distributes basic goods is not natural or inevitable: the order was painstakingly constructed by powerful interests. Shoplifting is only the most obvious surface manifestation of the social crisis this arrangement has caused.

Supermarkets Versus Socialism

It wasn’t easy to steal groceries before the early twentieth century. Shoppers patronized independent, “full-service” stores where products were stocked behind a counter so that only a clerk could access them. Knowledgeable about the merchandise they sold, grocers enjoyed a kind of professional status, and customers relied on them for advice. Since prices were not posted, clerks also determined how much each customer paid. Bargaining was common.

Everything changed thanks to a grocery entrepreneur named Clarence Saunders. One day, the story goes, the former Confederate soldier was looking out the window of a train when he saw some pigs dashing to a trough. According to writer Benjamin Lorr, Saunders imagined the pigs as shoppers forced to pass through a gate to peruse “heavily branded pre-packaged goods . . . that didn’t need a clerk to recommend them.” Choosing from a display of fixed-price products was a radical idea. No one had ever before been able to wander the aisles of a store full of food.

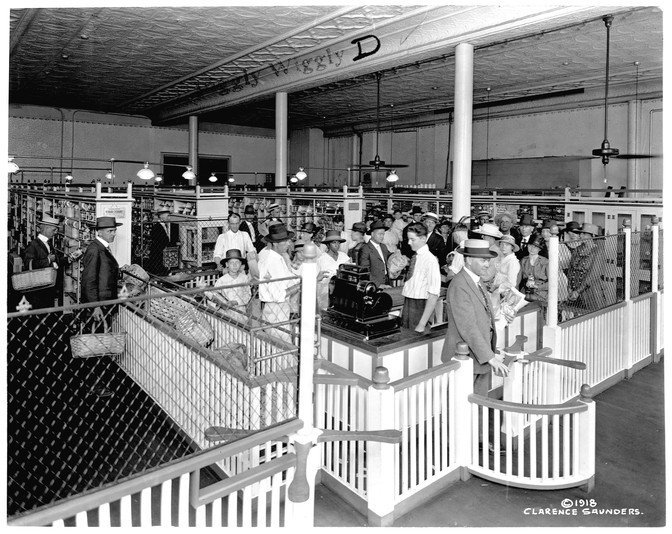

Saunders opened the first self-service grocery outlet in 1916 in Memphis and named it Piggly Wiggly, apparently in reference to those farm animals that had inspired him. Because merchandise was ordered from wholesalers, prices were lower than at independent stores. The new arrangement also lowered costs by de-skilling labor: since clerks’ new primary job was stocking shelves, they gave up their status as industry professionals. Customers were thrilled at the prospect of doing for themselves what was formerly done by paid employees. Piggly Wiggly was a phenomenon.

Self-service made retail shoplifting as we know it today possible. In recognition of the risk, Saunders built his first store with turnstiles, separate entrances and exits, and steel fencing. The design, Lorr writes, “evok[ed] a prison yard” more than a food outlet. For shoppers, being penned in like farm animals or like human criminals was a small price to pay for the freedom to handle, assess, and select their food.

The interior of the original Piggly Wiggly store in Memphis, Tennessee, 1918. Photo by Clifford H. Poland / Library of Congress

The rise of modern grocery shopping tracked with a broader economic shift, in which access to basic goods from health care and housing to food was mediated by large financial institutions. Wall Street money poured into the grocery industry, enabling Saunders to open more than twenty-five hundred Piggly Wigglies by the end of the 1930s. The Kroger corporation operated more than five thousand stores during the period. A&P, the Walmart of its day, dominated them all, with over fifteen thousand outlets in operation by the end of the decade.

The meteoric rise of grocery chains was not welcomed by everyone. As big retail chains stamped out independent grocers, critics complained that the stores destroyed the charm of small-town life and lowered wages. These days, with that battle decisively ended and the world remade by the victors, it’s difficult to imagine how fiercely the public debated the question of mass food distribution. In the 1930s, big retailers’ triumph was not a foregone conclusion: in response to anti-chain protests, twenty-six states imposed higher taxes on the biggest outlets.

Following the corporate takeover of the grocery business, and more broadly large capitalists’ role in the stock market crash and Great Depression, working-class people began to seek out more democratic forms of consumption. Enter the consumer cooperative, where members shared the labor of running stores and invested the profits back into their communities. By 1944, more than 1.5 million people had joined a cooperative, an increase of 800 percent from a few years before. Already constrained by state legislatures, retailers were suddenly also at war with progressive consumer-activists.

Black people were instrumental in developing a thriving cooperative movement. Barred from many stores due to Jim Crow laws in the South and racial discrimination in the North, blacks saw economic cooperation as a means of survival. It was a way to build on what the scholar Jessica Gordon Nembhard has called “a broad tradition of populism and economic justice,” and what W. E. B. Du Bois called the “spirit of revolt” that had begun during slavery.

One of the most successful cooperatives of the era was established in a Chicago housing project and named after the journalist and civil rights activist Ida B. Wells. The connection between Wells and the food distribution question was far from tenuous: Wells’s legendary career had begun in the 1890s with her investigation of the lynching of three men in Memphis — the same city where Saunders would later open the first Piggly Wiggly — after they opened the “People’s Grocery,” a cooperative that threatened a white grocer’s monopoly on the business.

Another black-led cooperative, the Young Negroes Cooperative League, was helmed by Ella Baker who would go on to lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King Jr. “The soil and all of its resources,” she said in a 1935 interview, “will be reclaimed by its rightful owners — the working masses of the world.” For the civil rights activist, economic cooperation among working people was a key to establishing socialism.

This militant and ambitious rhetoric explains why the cooperative consumer movement became a target of the anti-communist Red Scare starting in the late 1930s and lasting until the 1960s. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) leveled the sensational charge that nearly all consumer groups in the United States were led by communists. HUAC accused co-ops and consumer activists of attempting to “discredit free enterprise in the United States,” a charge that made newspaper headlines around the country.

The scholar Landon Storrs has argued that cooperative organizations were targeted with the same vitriol as the “labor, anti-fascist, and civil rights causes” that also came under attack during the era. The result was devastating to a movement committed to black liberation and economic cooperation. Amid the Red Scare, shoppers began to distance themselves from cooperative stores maligned as un-American.

As co-ops were being denounced as a Soviet plot, self-service retail outlets were being heralded as symbols of economic freedom. The State Department opened model stores in Europe in the 1950s to convince the continent’s consumers that capitalism filled bellies best. The scholar Tracey Deutsch described one international tour where shoppers in Southern and Eastern Europe “were treated to exhibits of . . . checkout lanes, refrigerated cases for produce and frozen foods, and . . . gravity defying towers of canned goods.” Customers flocked to the stores. “Heaven must be like this,” one shopper said in response to the abundance on display.

Sensing a propaganda coup, business leaders like Nelson Rockefeller began opening grocery stores across the Atlantic with little hope of turning an immediate profit. “The perceived power of supermarkets to sway people from communism,” Deutsch explained, “informed the construction of actual supermarkets by U.S. firms in Europe.” Grocery stores had become anti-communist icons, an ideological victory more important to companies than profits.

Today, co-ops are often dismissed as offbeat boutiques frequented by hippies and the upper classes, while the vast majority of us shop in supermarkets.

The Triumph of Big Retail

The federally funded offensive to elevate retail chains as bastions of free-market capitalism while crushing democratic alternatives is the historical backdrop to today’s “great shoplifting freakout.”

Whether or not media reports of a crime surge are accurate, retail theft occurs frequently in our society — and the material basis for shoplifting has worsened over the last few years. A corporate food system that profits from “just-in-time” delivery led to empty shelves and panic buying during the pandemic and, more recently, to record-high inflation. Groceries are getting much harder for the average working-class American to afford. Yet even as the cost of groceries has skyrocketed, the concept of a privatized food distribution system is so hegemonic that other forms of mass provisioning are hard to imagine.

I began researching the grocery industry in part to absolve myself of guilt for having assisted in the capture of the donut thief. A better understanding of systemic causes, however, did not make me feel less implicated in the encounters between shoplifters and store employees that I observed on the job. I looked forward to the day when I would no longer have to feel like I was guarding the border between basic goods and the people who couldn’t afford them. But by the time I left the store, I knew that being on the other side of the checkstand offered no redemption.

Security personnel like John are hired to protect property. They also uphold the widely supported moral belief that people should not be able to steal and that stores should be pleasant places free of the social tensions that shoplifters bring. Like the prison guards featured in Eyal Press’s Dirty Work, grocery store guards are “necessary to the prevailing social order.” They solve “various ‘problems’ that many Americans want taken care of but don’t want to have to think too much about, much less handle themselves.” Once I transitioned from employee to customer, thieves would be tased and arrested on my behalf.

The propaganda campaign that helped to consolidate the commercial grocery industry has continued to the point where there is little public outcry about the fact that a handful of megacorporations now controls almost 80 percent of the market. One reason Big Retail has triumphed for so long is because stores are often community pillars that offer small pleasures in addition to basic goods. It’s hard to see them as the inherently exploitative, exclusionary, and violent places that they are — especially if the security guard isn’t coming after you.

Another reason for the industry’s durability is that, in the grocery store, Clarence Saunders’s original sleight of hand still works its magic. Aisles of products are out in the open, apparently available to anyone who wants them. Shoplifting disturbs and distresses because it reveals our broader social predicament: we are free to shop for what we need to live within the confines of a surveilled space. But we must pay the posted price to get out.

Ann Larson is a writer whose work has appeared in the New Republic, the Nation, and the Chronicle of Higher Education, among other publications. She lives in Utah.