By The Mapping Project

Republished from Monthly Review.

The greatest threat looming over our planet, the hegemonistic pretentions of the American Empire are placing at risk the very survival of the human species. We continue to warn you about this danger, and we appeal to the people of the United States and the world to halt this threat, which is like a sword hanging over our heads.

–Hugo Chavez

The United States Military is arguably the largest force of ecological devastation the world has ever known.

–Xoài Pham

Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, and fulfill it or betray it.

–Frantz Fanon

U.S. imperialism is the greatest threat to life on the planet, a force of ecological devastation and disaster impacting not only human beings, but also our non-human relatives. How can we organize to dismantle the vast and complicated network of U.S. imperialism which includes U.S. war and militarism, CIA intervention, U.S. weapons/technology/surveillance corporations, political and economic support for dictatorships, military juntas, death squads and U.S. trained global police forces favorable to U.S. geopolitical interests, U.S. imposed sanctions, so-called “humanitarian interventions,” genetically modified grassroots organizations, corporate media’s manipulation of spontaneous protest, and U.S. corporate sponsorship of political repression and regime change favorable to U.S. corporate interests?

This article deals with U.S. imperialism since World War 2. It is critical to acknowledge that U.S. imperialism emanates both ideologically and materially from the crime of colonialism on this continent which has killed over 100 million indigenous people and approximately 150 million African people over the past 500 years.

The exact death toll of U.S. imperialism is both staggering and impossible to know. What we do know is that since World War 2, U.S. imperialism has killed at least 36 million people globally in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, the Congo, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Chad, Libya, East Timor, Grenada, Honduras, Iran, Pakistan, Panama, the Philippines, Sudan, Greece, Yugoslavia, Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, Somalia, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Palestine (see Appendix).

This list does not include other aspects of U.S. imperialist aggression which have had a devastating and lasting impact on communities worldwide, including torture, imprisonment, rape, and the ecological devastation wrought by the U.S. military through atomic bombs, toxic waste and untreated sewage dumping by over 750 military bases in over 80 countries. The U.S. Department of Defense consumes more petroleum than any institution in the world. In the year of 2017 alone, the U.S. military emitted 59 million metric tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, a carbon footprint greater than that of most nations worldwide. This list also does not include the impact of U.S. fossil fuel consumption and U.S. corporate fossil fuel extraction, fracking, agribusiness, mining, and mono-cropping, all of which are part and parcel of the extractive economy of U.S. imperialism.

U.S. military bases around the world. (Photo: Al Jazeera)

One central mechanism of U.S. imperialism is “dollar hegemony” which forces countries around the world to conduct international trade in U.S. dollars. U.S. dollars are backed by U.S. bonds (instead of gold or industrial stocks) which means a country can only cash in one American IOU for another. When the U.S. offers military aid to friendly nations, this aid is circulated back to U.S. weapons corporations and returns to U.S. banks. In addition, U.S. dollars are also backed by U.S. bombs: any nation that threatens to nationalize resources or go off the dollar (i.e. Iraq or Libya) is threatened with a military invasion and/or a U.S. backed coup.

U.S. imperialism has also been built through “soft power” organizations like USAID, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), World Bank, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Organization of American States (OAS). These nominally international bodies are practically unilateral in their subservience to the interests of the U.S. state and U.S. corporations. In the 1950s and ‘60s, USAID (and its precursor organizations) made “development aid” to Asian, African, and South American countries conditional on those countries’ legal formalization of capitalist property relations, and reorganization of their economies around homeownership debt. The goal was to enclose Indigenous land, and land shared through alternate economic systems, as a method of “combatting Communism with homeownership” and creating dependency and buy-in to U.S. capitalist hegemony (Nancy Kwak, A World of Homeowners). In order to retain access to desperately needed streams of resources (e.g. IMF “loans”), Global South governments are forced to accept resource-extraction by the U.S., while at the same time denying their own people popularly supported policies such as land reform, economic diversification, and food sovereignty. It is also important to note that Global South nations have never received reparations or compensation for the resources that have been stolen from them–this makes the idea of “loans” by global monetary institutions even more outrageous.

The U.S. also uses USAID and other similarly functioning international bodies to suppress and to undermine anti-imperialist struggle inside “friendly” countries. Starting in the 1960s, USAID funded police training programs across the globe under a counterinsurgency model, training foreign police as a “first line of defense against subversion and insurgency.” These USAID-funded police training programs involved surveillance and the creation of biometric databases to map entire populations, as well as programs of mass imprisonment, torture, and assassination. After experimenting with these methods in other countries, U.S. police departments integrated many of them into U.S. policing, especially the policing of BIPOC communities here (see our entry on the Boston Police Department). At the same time, the U.S. uses USAID and other soft power funding bodies to undermine revolutionary, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist movements, by funding “safe” reformist alternatives, including a global network of AFL-CIO managed “training centers” aimed at fostering a bureaucratic union culture similar to the one in the U.S., which keeps labor organizing loyal to capitalism and to U.S. global dominance. (See our entries on the AFL-CIO and the Harvard Trade Union Program.)

U.S. imperialism intentionally fosters divisions between different peoples and nations, offering (relative) rewards to those who choose to cooperate with U.S. dictates (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Colombia), while brutally punishing those who do not (e.g. Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela). In this way, U.S. imperialism creates material conditions in which peoples and governments face a choice: 1. accommodate the interests of U.S. Empire and allow the U.S. to develop your nation’s land and sovereign resources in ways which enrich the West; or, 2. attempt to use your land and your sovereign resources to meet the needs of your own people and suffer the brutality of U.S. economic and military violence.

The Harvard Kennedy School: Training Ground for U.S. Empire and the Security State

The Mapping Project set out to map local U.S. imperialist actors (involved in both material and ideological support for U.S. imperialism) on the land of Massachusett, Pawtucket, Naumkeag, and other tribal nations (Boston, Cambridge, and surrounding areas) and to analyze how these institutions interacted with other oppressive local and global institutions that are driving colonization of indigenous lands here and worldwide, local displacement/ethnic cleansing (“gentrification”), policing, and zionist imperialism.

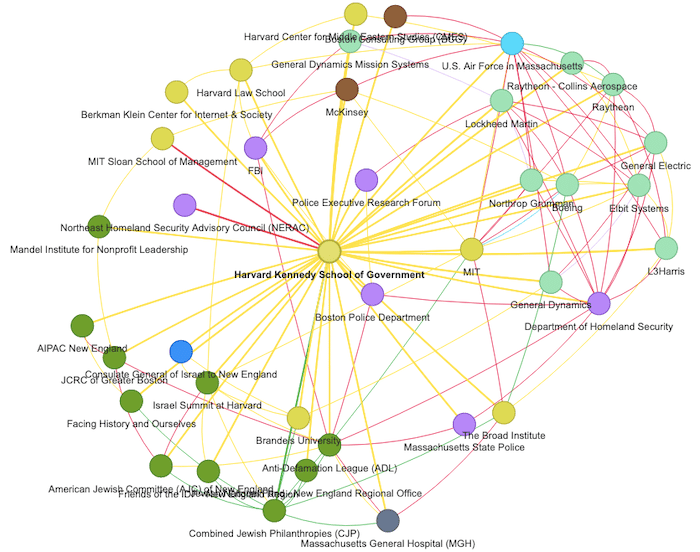

A look at just one local institution on our map, the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, demonstrates the level of ideological and material cooperation required for the machinery of U.S. imperialism to function. (All information outlined below is taken from The Mapping Project entries and links regarding the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Please see this link for hyperlinked source material.)

The Harvard Kennedy School of Government and its historical precursors have hosted some of the most infamous war criminals and architects of empire: Henry Kissinger, Samuel Huntington, Susan Rice (an HKS fellow), Madeleine Albright, James Baker, Hillary Clinton, Colin Powell, Condoleeza Rice, and Larry Summers. HKS also currently hosts Ricardo Hausmann, founder and director of Harvard’s Growth Lab , the academic laboratory of the U.S. backed Venezuelan coup.

In How Harvard Rules, John Trumpbour documents the central role Harvard played in the establishment of the Cold War academic-military-industrial complex and U.S. imperialism post-WWII (How Harvard Rules, 51). Trumpbour highlights the role of the Harvard Kennedy School under Dean Graham Allison (1977-1989), in particular, recounting that Dean Allison ran an executive education program for Pentagon officials at Harvard Kennedy (HHR 68). Harvard Kennedy School’s support for the U.S. military and U.S. empire continues to this day. HKS states on its website:

Harvard Kennedy School, because of its mission to train public leaders and its depth of expertise in the study of defense and international security, has always had a particularly strong relationship with the U.S. Armed Forces. This relationship is mutually beneficial. The School has provided its expertise to branches of the U.S. military, and it has given military personnel (active and veteran) access to Harvard’s education and training.

The same webpage further notes that after the removal of ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps) from Harvard Kennedy School in 1969, “under the leadership of Harvard President Drew Faust, the ROTC program was reinstated in 2011, and the Kennedy School’s relationship with the military continues to grow more robust each year.”

In particular, Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs provides broad support to the U.S. military and the objectives of U.S. empire. The Belfer Center is co-directed by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter (a war hawk who has advocated for a U.S. invasion of North Korea and U.S. military build ups against Russia and Iran) and former Pentagon Chief of Staff Eric Rosenbach. Programs within HKS Belfer Center include the Center’s “Intelligence Program,” which boasts that it “acquaints students and Fellows with the intelligence community and its strengths and weaknesses for policy making,” further noting, “Discussions with active and retired intelligence practitioners, scholars of intelligence history, law, and other disciplines, help students and Fellows prepare to best use the information available through intelligence agencies.” Alongside HKS Belfer’s Intelligence Program, is the Belfer Center’s “Recanati-Kaplan Foundation Fellowship.” The Belfer Center claims that, under the direction of Belfer Center co-directors Ashton Carter and Eric Rosenbach, the Recanati-Kaplan Foundation Fellowship “educates the next generation of thought leaders in national and international intelligence.”

As noted above, the Harvard Kennedy School serves as an institutional training ground for future servants of U.S. empire and the U.S. national security state. HKS also maintains a close relationship with the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). As reported by Inside Higher Ed in their 2017 review of Spy Schools by Daniel Golden:

[Harvard Kennedy School] currently allows the agency [the CIA] to send officers to the midcareer program at the Kennedy School of Government while continuing to act undercover, with the school’s knowledge. When the officers apply–often with fudged credentials that are part of their CIA cover–the university doesn’t know they’re CIA agents, but once they’re in, Golden writes, Harvard allows them to tell the university that they’re undercover. Their fellow students, however–often high-profile or soon-to-be-high-profile actors in the world of international diplomacy–are kept in the dark.

Kenneth Moskow is one of a long line of CIA officers who have enrolled undercover at the Kennedy School, generally with Harvard’s knowledge and approval, gaining access to up-and-comers worldwide,” Golden writes. “For four decades the CIA and Harvard have concealed this practice, which raises larger questions about academic boundaries, the integrity of class discussions and student interactions, and whether an American university has a responsibility to accommodate U.S. intelligence.”

In addition to the CIA, HKS has direct relationships with the FBI, the U.S. Pentagon, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, NERAC, and numerous branches of the U.S. Armed Forces:

Chris Combs, a Senior Fellow with HKS’s Program on Crisis Leadership has held numerous positions within the FBI;

Jeffrey A. Tricoli, who serves as Section Chief of the FBI’s Cyber Division since December 2016 (prior to which he held several other positions within the FBI) was a keynote speaker at “multiple sessions” of the HKS’s Cybersecurity Executive Education program;

Jeff Fields, who is Fellow at both the Cyber Project and the Intelligence Project of HKS’s Belfer Center currently serves as a Supervisory Special Agent within the National Security Division of the FBI;

HKS hosted former FBI director James Comey for a conversation with HKS Belfer Center’s Co-Director (and former Pentagon Chief of Staff) Eric Rosenbach in 2020;

Government spending records show yearly tuition payments from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for Homeland Security personnel attending special HKS seminars on Homeland Security under HKS’s Program on Crisis Leadership;

Northeast Homeland Security Regional Advisory Council meeting minutes from February 2022 list “Edward Chao: Analyst, Harvard Kennedy School,” as a NERAC “Council Member”; and

Harvard Kennedy School and the U.S. Air force have created multiple fellowships aimed at recruiting U.S. Air Force service members to pursue degrees at HKS. The Air Force’s CSAF Scholars Master Fellowship, for example, aims to “prepare mid-career, experienced professionals to return to the Air Force ready to assume significant leadership positions in an increasingly complex environment.” In 2016, Harvard Kennedy School Dean Doug Elmendorf welcomed Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James to Harvard Kennedy School, in a speech in which Elmendorf highlighted his satisfaction that the ROTC program, including Air Force ROTC, had been reinstated at Harvard (ROTC had been removed from campus following mass faculty protests in 1969).

Harvard Kennedy School’s web.

The Harvard Kennedy School and the War Economy

HKS’s direct support of U.S. imperialism does not limit itself to ideological and educational support. It is deeply enmeshed in the war economy driven by the interests of the U.S. weapons industry.

Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Boeing, L3 Harris, General Dynamics, and Northrup Grumman are global corporations who supply the United States government with broad scale military weaponry and war and surveillance technologies. All these companies have corporate leadership who are either alumni of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government (HKS), who are currently contributing to HKS as lecturers/professors, and/or who have held leadership positions in U.S. federal government.

Lockheed Martin Vice President for Corporate Business Development Leo Mackay is a Harvard Kennedy School alumnus (MPP ’91), was a Fellow in the HKS Belfer Center International Security Program (1991-92) and served as the “military assistant” to then U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy Ashton Carter, who would soon go on to become co-director of the Harvard Kennedy School Belfer Center. Following this stint at the U.S. Pentagon, Mackay landed in the U.S. weapons industry at Lockheed Martin. Lockheed Martin Vice President Marcel Lettre is an HKS alumni and prior to joining Lockheed Martin, Lettre spent eight years in the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). The U.S. DoD has dished out a whopping $540.82 billion to date in contracts with Lockheed Martin for the provision of products and services to the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and other branches of the U.S. military. Lockheed Martin Board of Directors member Jeh Johnson has lectured at Harvard Kennedy School and is the former Secretary of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the agency responsible for carrying out the U.S. federal government’s regime of tracking, detentions, and deportations of Black and Brown migrants. (Retired) General Joseph F. Dunford is currently a member of two Lockheed Martin Board of Director Committees and a Senior Fellow with HKS’s Belfer Center. Dunford was a U.S. military leader, serving as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Commander of all U.S. and NATO Forces in Afghanistan. Dunford also serves on the board of the Atlantic Council, itself a cutout organization of NATO and the U.S. security state which crassly promotes the interests of U.S. empire. Mackay, Lettre, Johnson, and Dunford’s respective career trajectories provide an emblematic illustration of the grotesque revolving door which exists between elite institutions of knowledge production like the Harvard Kennedy School, the U.S. security state (which feeds its people into those elite institutions and vice versa), and the U.S. weapons industry (which seeks business from the U.S. security state).

Similar revolving door phenomena are notable among the Harvard Kennedy School and Raytheon, Boeing, and Northrup Grumman. HKS Professor Meghan O’Sullivan currently serves on the board of Massachusetts-based weapons manufacturer Raytheon. O’Sullivan is also deeply enmeshed within America’s security state, currently sitting on the Board of Directors of the Council on Foreign Relations and has served as “special assistant” to President George W. Bush (2004-07) where she was “Deputy National Security Advisor for Iraq and Afghanistan,” helping oversee the U.S. invasions and occupations of these nations during the so-called “War on Terror.” O’Sullivan has openly attempted to leverage her position as Harvard Kennedy School to funnel U.S. state dollars into Raytheon: In April 2021, O’Sullivan penned an article in the Washington Post entitled “It’s Wrong to Pull Troops Out of Afghanistan. But We Can Minimize the Damage.” As reported in the Harvard Crimson, O’Sullivan’s author bio in this article highlighted her position as a faculty member of Harvard Kennedy (with the perceived “expertise” affiliation with HKS grants) but failed to acknowledge her position on the Board of Raytheon, a company which had “a $145 million contract to train Afghan Air Force pilots and is a major supplier of weapons to the U.S. military.” Donn Yates who works in Domestic and International Business Development at Boeing’s T-7A Redhawk Program was a National Security Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School in 2015-16. Don Yates also spent 23 years in the U.S. Air Force. Former Northrop Grumman Director for Strategy and Global Relations John Johns is a graduate of Harvard Kennedy’s National and International Security Program. Johns also spent “seven years as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Maintenance establishing policy for, and leading oversight of the Department’s annual $80B weapon system maintenance program and deployed twice in support of security operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

The largest U.S. oil firms are also closely interlocked with these top weapons companies, which have also diversified their technological production for the security industry–providing services for pipeline and energy facility security, as well as border security. This means that the same companies are profiting at every stage in the cycle of climate devastation: they profit from wars for extraction; from extraction; and from the militarized policing of people forced to migrate by climate disaster. Exxon Mobil (the 4th largest fossil fuel firm) contracts with General Dynamics, L3 Harris, and Lockheed Martin. Lockheed Martin, the top weapons company in the world, shares board members with Chevron, and other global fossil fuel companies. (See Global Climate Wall: How the world’s wealthiest nations prioritise borders over climate action.)

The Harvard Kennedy School and U.S. Support for Israel

U.S. imperialist interests in West Asia are directly tied to U.S. support of Israel. This support is not only expressed through tax dollars but through ideological and diplomatic support for Israel and advocacy for regional normalization with Israel.

Harvard Kennedy School is home to the Wexner Foundation. Through its “Israel Fellowship,” The Wexner Foundation awards ten scholarships annually to “outstanding public sector directors and leaders from Israel,” helping these individuals to pursue a Master’s in Public Administration at the Kennedy School. Past Wexner fellows include more than 25 Israeli generals and other high-ranking military and police officials. Among them is the Israeli Defense Force’s current chief of general staff, Aviv Kochavi, who is directly responsible for the bombardment of Gaza in May 2021. Kochavi also is believed to be one of the 200 to 300 Israeli officials identified by Tel Aviv as likely to be indicted by the International Criminal Court’s probe into alleged Israeli war crimes committed in Gaza in 2014. The Wexner Foundation also paid former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak–himself accused of war crimes in connection with Israel’s 2009 Operation Cast Lead that killed over 1,400 Palestinians in Gaza–$2.3 million for two studies, one of which he did not complete.

HKS’s Belfer Center has hosted Israeli generals, politicians, and other officials to give talks at Harvard Kennedy School. Ehud Barak, mentioned above, was himself a “Belfer fellow” at HKS in 2016. The Belfer Center also hosts crassly pro-Israel events for HKS students, such as: The Abraham Accords – A conversation on the historic normalization of relations between the UAE, Bahrain and Israel,” “A Discussion with Former Mossad Director Tamir Pardo,” “The Future of Modern Warfare” (which Belfer describes as “a lunch seminar with Yair Golan, former Deputy Chief of the General Staff for the Israel Defense Forces”), and “The Future of Israel’s National Security.”

As of 2022, Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center is hosting former Israel military general and war criminal Amos Yadlin as a Senior Fellow at the Belfer’s Middle East Initiative. Furthermore, HKS is allowing Yadlin to lead a weekly study group of HKS students entitled “Israeli National Security in a Shifting Middle East: Historical and Strategic Perspectives for an Uncertain Future.” Harvard University students wrote an open letter demanding HKS “sever all association with Amos Yadlin and immediately suspend his study group.” Yadlin had defended Israel’s assassination policy through which the Israeli state has extrajudicially killed hundreds of Palestinians since 2000, writing that the “the laws and ethics of conventional war did not apply” vis-á-vis Palestinians under zionist occupation.

Harvard Kennedy School also plays host to the Harvard Kennedy School Israel Caucus. The HKS Israel Caucus coordinates “heavily subsidized” trips to Israel for 50 HKS students annually. According to HKS Israel Caucus’s website, students who attend these trips “meet the leading decision makers and influencers in Israeli politics, regional security and intelligence, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, [and] the next big Tech companies.” The HKS Israel Caucus also regularly hosts events which celebrate “Israel’s culture and history.” Like the trips to Israel they coordinate, HKS Israel Caucus events consistently whitewash over the reality of Israel’s colonial war against the Palestinian people through normalizing land theft, forced displacement, and resource theft.

Harvard Kennedy School also has numerous ties to local pro-Israel organizations: the ADL, the JCRC, and CJP.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s Support for Saudi Arabia

In 2017, Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center announced the launch of “The Project on Saudi and Gulf Cooperation Council Security,” which Belfer stated was “made possible through a gift from HRH Prince Turki bin Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia.” Through this project, Harvard Kennedy School and the HKS Belfer Center have hosted numerous events at HKS which have promoted Saudi Arabia as a liberalizing and positive force for security and stability in the region, whitewashing over the realities of the Saudi-led and U.S.-backed campaign of airstrikes and blockade against Yemen which has precipitated conditions of mass starvation and an epidemic of cholera amongst the Yemeni people.

The Belfer Center’s Project on Saudi and Gulf Cooperation Council Security further normalizes and whitewashes Saudi Arabia’s crimes through its “HKS Student Delegation to Saudi Arabia.” This delegation brings 11 Harvard Kennedy School students annually on two-week trips to Saudi Arabia, where students “exchange research, engage in cultural dialogue, and witness the changes going on in the Kingdom firsthand.” Not unlike the student trips to Israel Harvard Kennedy School’s Israel Caucus coordinates, these trips to Saudi Arabia present HKS students with a crassly propagandized impression of Saudi Arabia, shoring up support for the “Kingdom” amongst the future leaders of the U.S. security state which HKS seeks to nurture.

THE MAPPING PROJECT’S Mission

The vast network outlined above between the Harvard Kennedy School, the U.S. federal government, the U.S. Armed Forces, and the U.S. weapons industry constitutes only a small portion of what is known about HKS and its role in U.S. imperialism, but it is enough.

The Mapping Project demonstrates that the Harvard Kennedy School of Government is a nexus of U.S. imperialist planning and cooperation, with an address. The Mapping Project also links HKS to harms locally, including, but not limited to colonialism, violence against migrants, ethnic cleansing/displacement of Black and Brown Boston area residents from their communities (“gentrification”), health harm, policing, the prison-industrial complex, zionism, and surveillance. The Harvard Kennedy School’s super-oppressor status – the sheer number of separate communities feeling its global impact in their daily lives through these multiple and various mechanisms of oppression and harm – as it turns out, is its greatest weakness.

A movement that can identify super-oppressors like the Harvard Kennedy School of Government can use this information to identify strategic vulnerabilities of key hubs of power and effectively organize different communities towards common purpose. This is what the Mapping Project aims to do–to move away from traditionally siloed work towards coordination across communities and struggles in order to build strategic oppositional community power.

Appendix: The Death Toll of U.S. Imperialism Since World War 2

A critical disclaimer: Figures relating to the death toll of U.S. Imperialism are often grossly underestimated due to the U.S. government’s lack of transparency and often purposeful coverup and miscounts of death tolls. In some cases, this can lead to ranges of figures that include millions of human lives–as in the figure for Indonesia below with estimates of 500,000 to 3 million people. We have tried to provide the upward ranges in these cases since we suspect the upward ranges to be more accurate if not still significantly underestimated. These figures were obtained from multiple sources including but not limited to indigenous scholar Ward Churchill’s Pacifism as Pathology as well as Countercurrents’ article Deaths in Other Nations Since WWII Due to U.S. Interventions (please note that use of Countercurrents’ statistics isn’t an endorsement of the site’s politics).

Afghanistan: at least 176,000 people

Bosnia: 20,000 to 30,000 people

Bosnia and Krajina: 250,000 people

Cambodia: 2-3 million people

Chad: 40,000 people and as many as 200,000 tortured

Chile: 10,000 people (the U.S. sponsored Pinochet coup in Chile)

Colombia: 60,000 people

Congo: 10 million people (Belgian imperialism supported by U.S. corporations and the U.S. sponsored assassination of Patrice Lumumba)

Croatia: 15,000 people

Cuba: 1,800 people

Dominican Republic: at least 3,000 people

East Timor: 200,000 people

El Salvador: More than 75,000 people (U.S. support of the Salvadoran oligarchy and death squads)

Greece: More than 50,000 people

Grenada: 277 people

Guatemala: 140,000 to 200,000 people killed or forcefully disappeared (U.S. support of the Guatemalan junta)

Haiti: 100,000 people

Honduras: hundreds of people (CIA supported Battalion kidnapped, tortured and killed at least 316 people)

Indonesia: Estimates of 500,000 to 3 million people

Iran: 262,000 people

Iraq: 2.4 million people in Iraq war, 576, 000 Iraqi children by U.S. sanctions, and over 100,000 people in Gulf War

Japan: 2.6-3.1 million people

Korea: 5 million people

Kosovo: 500 to 5,000

Laos: 50,000 people

Libya: at least 2500 people

Nicaragua: at least 30,000 people (U.S. backed Contras’ destabilization of the Sandinista government in Nicaragua)

Operation Condor: at least 10,000 people (By governments of Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru. U.S. govt/CIA coordinated training on torture, technical support, and supplied military aid to the Juntas)

Pakistan: at least 1.5 million people

Palestine: estimated more than 200,000 people killed by military but this does not include death from blockade/siege/settler violence

Panama: between 500 and 4000 people

Philippines: over 100,000 people executed or disappeared

Puerto Rico: 4,645-8,000 people

Somalia: at least 2,000 people

Sudan: 2 million people

Syria: at least 350,000 people

Vietnam: 3 million people

Yemen: over 377,000 people

Yugoslavia: 107,000 people