By Bernardo Jurema and Elias Koenig

This is a summary of the paper ‘State Power and Capital in the Climate Crisis: A Theory of Fossil Imperialism,’ presented by the authors during the “Confronting Climate Coloniality” - Paper Session at the American Association of Geographers (AAG) annual meeting on March 26th, 2023. It is also an overview of some of the main ideas that we hope to further develop this year. While the research behind the conference paper was carried out at Research Institute for Sustainability - Helmholtz Centre Potsdam (RIFS), the opinions and viewpoints expressed herein are our own and do not represent the standpoints of RIFS as a whole. This piece was originally published on the RIFS Potsdam website.

In recent years, both activists and researchers have started to invoke the term fossil imperialism to highlight the ways in which imperialist politics are tied up with the logic of fossil capitalism. Under fossil capitalism, ceaseless accumulation of capital necessitates continued expansion of an energy base of coal, oil, and natural gas. Imperial states play a key role in the process, which has in turn enabled a remarkable concentration of imperial power and continues to do so in today’s world order. Understanding fossil imperialism, therefore, is necessary for devising effective strategies of resistance to a planet-wrecking capitalist status quo.

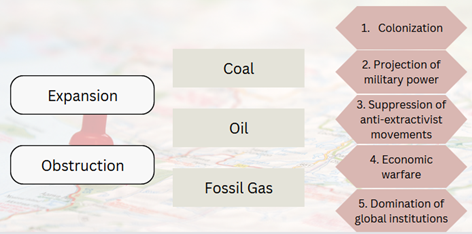

Our model of fossil imperialism attempts to sketch the general workings of this relationship between imperial states and fossil capital in its historical development over the past two centuries and in its different varieties. It is principally based on the two general modes of expansion and obstruction. On the one hand, the expansion and protection of new fossil fuel resources and infrastructure are crucial to keeping the engine rooms of fossil capital well-supplied. On the other hand, the obstruction or destruction of the infrastructure of rivaling capital factions and states in order to maintain control over pricing and distribution has been equally integral to the history of fossil imperialism. In this way, the workings of fossil imperialism reflect the more general nature of capitalism as a mode of production and destruction.

It is important to take into account the specific characteristics of the three dominant sources of fossil energy (coal, oil, gas) when analyzing concrete cases. While all three energy sources still hold a significant share of the global fossil economy, each also corresponds to a distinct historical phase in the development of fossil imperialism. Coal powered the rise of the British Empire, the switch to oil marked the ascent of American hegemony in the 20th century, and fossil gas is increasingly at the core of the United States’ attempt to continue projecting its supremacy well into the 21st century. While there is growing concern over new forms of "green imperialism", especially in relation to the extraction and distribution of the raw materials supposedly required to decarbonize the economies of the North, current fossil-fueled conflicts such as the Russian war in Ukraine or the Saudi war in Yemen show that the age of fossil imperialism is - unfortunately - far from over.

There are at least five ways in which imperial states facilitate the interests of fossil capital: through colonization, the projection of military power, the suppression of anti-extractivist movements, economic warfare, and the domination of global institutions. This scheme makes plain the crucial role of fossil fuels, functioning variously as a driver, as an enhancer or as an outcome of imperial states' actions. It disentangles the ways in which contemporary politics are significantly influenced by fossil fuels, which have played a defining role in shaping the structure of capitalist corporations, settler-imperial states, and earth-transforming technoscience. These arrangements have had profound consequences for ecological destruction and the implementation of ecological management strategies.

Colonization is a form of direct political domination and subjugation of one people by another. It was perhaps most evident during the “golden” age of coal, the fossil fuel that powered the rise of the British Empire — from Australia to India, from South Africa to Borneo. Because coal extraction requires a large amount of disciplined labor, arguably, it also necessitates more comprehensive forms of social and political control than oil and gas extraction. At the same time, the British — in many cases — obstructed the rapid expansion of foreign coal industries to protect their own domestic industry. Even in the case of oil and gas, many of the major private companies like BP and Shell still operate in markets shaped by colonial legacies.

“Projection of military power” refers to different kinds of military interventions short of full-on colonization. Historically, states often deployed their own forces to protect fossil infrastructure abroad — a practice that continues today in various ways. Projection of military power also takes place through proxy armies, funded through a closed circuit of oil money and weapons contracts, as in the case of the Gulf monarchies. The 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq reminds us how current the role of military power remains. Twenty years after the regime-change military intervention, the United States still has 2500 troops stationed in the country. And, as has recently been revealed, BP and Shell, which had been barred from the country for decades, have extracted tens of billions of dollars in Iraqi oil post-invasion.

The pursuit of regional economic dominance on the part of fossil imperial states requires the suppression of anti-extractivist movements and other grassroots movements opposed to the social order. Interventionary military assistance was justified from the 1990s onwards on the basis of immigration enforcement, anti-narcotics control, and fighting against general criminality. For example, the role of the War on Drugs in continuing counterinsurgent practices against civilian population that were carried out until the late 1980s within a Cold War framework. However, according to Russell Crandall, professor at Davidson College in North Carolina and former Pentagon and National Security Council official under George W. Bush, the significant role in shaping outcomes is not primarily played by the U.S. military advisors, but rather by the "imperial diplomats" – the civilian officials within the U.S. foreign policy structure.

In his study of economic sanctions, Cornell historian Nicholas Mulder has demonstrated that modern-day sanctions developed out of mechanisms for energy control, blacklisting, import and export rationing, property seizures and asset freezes, trade prohibitions, and preclusive purchasing, as well as financial blockade — simply put, economic warfare. He shows that effectively isolating a whole nation from the intricate networks that support global trade requires the ability to gather information and generate knowledge. This involves mapping the intricate web of physical goods and resources that connect the specific country to the rest of the globe. Key factors in this process include having legal authority and access to more precise data and statistics. What makes it possible to impose this unilateral sanctions regime on the rest of the world is the domination of the global (financial and political) institutions that regulate the trade and distribution of fossil fuels. Both 19th-century British and 20th-century US-American dominance stemmed from their respective global leadership in corporate, regulatory, technological, and financial frameworks, which in turn was tightly linked to the pound sterling and later the US dollar being the chief reserve and trade currencies of their time.

In the age of American hegemony, the United Nations and other multilateral organizations — in particular, the Bretton Woods system (the International Monetary Fund and World Bank) — have become key means to maintain its armed primacy and fossil-based economic dominance. Significantly, the US-led bloc thwarted attempts by the newly decolonized countries in the postwar period to build a fairer world order by torpedoing the Third World agenda, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the Non-Aligned Movement and the New International Economic Order.

Conclusion

It is impossible to understand imperialism without understanding the role of fossil fuels in its historical emergence and development. A climate movement that does not actively take into account the mechanisms of fossil imperialism risks being co-opted into imperialist false solutions to the climate crisis. Likewise, anti-imperial movements that fail to break definitively with the logic of fossil capitalism historically fall victim to various social and ecological contradictions. A case in point are the Pink Tide governments of the first decade of the 21st century. As University of Toronto political scientist Donald Kingsbury put it, when "faced with a choice between extraction and the local movements that made their governments possible,” these regimes “sided with extraction." A better understanding of the topic can therefore contribute to more effective climate justice activism, more strategic clarity and tactical innovation, and serve as a basis for more international solidarity.