[ILLUSTRATION BY ALEX NABAUM]

By Peter S. Baron

A major obstacle to the collective well-being of workers is how corporate employers connect retirement funds to the stock market. This linking means that workers bear the brunt, as publicly traded companies aim to maximize profitability through cost-cutting measures that negatively impact their wages, job security, and working conditions. Similarly, labor unions like the United Auto Workers (UAW) channel membership dues into investment funds that often hold stocks in the very companies they may confront or negotiate with.

Recent history has witnessed a significant transformation in the structure of labor's retirement portfolios; they are now primarily sustained by individual contributions, with companies only occasionally offering modest matching contributions. Individuals now shoulder the entire risk, while corporations benefit from reduced financial liabilities and greater predictability in managing retirement expenses. Insidiously, as corporations have shifted financial risk onto individuals, they have also directed these investments toward financial management behemoths. These entities hold control over each individual investor’s voting rights, effectively seizing the collective power of working-class retirement funds. This power is then leveraged to amplify the relentless profit-driven mechanisms at the core of capitalism. Running parallel, organized labor’s advocacy power has been undermined by union bureaucrats who have chosen to tether the union's financial health to the success of the same corporate giants it should be challenging, effectively making the union a complacent, and likely complicit, partner in the very corporate strategies that exploit its members.

These financial realities, carefully engineered by corporations and meekly accepted by labor, are riddled with contradictions that reveal the blatant exploitation at the core of the elite’s oppression of workers. They serve as stark reminders that security and well-being, let alone collective liberation, won't come from corporate investment schemes or the leadership of corporate bureaucratic puppets, but only from the solidarity and unified strength of the workforce. The power to dismantle this exploitation lies in workers rejecting the illusion of corporate benevolence and instead building unwavering unity to reclaim their future through collective action.

Background

Traditionally, workers' retirement funds were managed through Defined Benefit (DB) plans, which ensured a stable pension for retirees and placed the investment risk on employers, who shouldered the costs of employees' retirement benefits. Though these DB plans were similarly invested in the stock market, the companies themselves were responsible for ensuring that the retirement fund has enough resources to meet those guaranteed payouts, meaning the employer must cover any shortfall if investment returns do not meet expectations. These plans became seen as economically burdensome by corporate executives who aimed to maintain steadily growing profits in an era marked by rapid market shifts and increasing global competition (https://livewell.com/finance/why-have-employers-moved-from-defined-benefit-to-defined-contribution-plans/).

The transition to 401(k) and other Defined Contribution (DC) plans offloaded these risks onto employees, fundamentally transforming the nature of retirement savings. Defined Contribution plans prioritize contributions over guaranteed payouts, requiring employers and workers to allocate set amounts into individual retirement accounts. With the employer no longer liable to provide a guaranteed income, workers must now shoulder the burden of their own retirement funding, gambling their hard-earned savings in the unpredictable stock market. Though favorable returns can occur, sustained gains are elusive due to regular market crashes that occur every six years on average. This means that when the market plummets, it's the employees who bear the brunt, not the employers, exposing workers' financial security to the whims of an unstable market while leaving them vulnerable to navigating a system designed to shift the risks and costs of retirement away from corporations.

The neoliberal ideological shift that encouraged employers to search for cost-cutting measures also aligned with broader economic changes, including a shift from manufacturing to service and IT sectors, where new companies were more likely to adopt DC plans. Furthermore, legislation like the Pension Protection Act of 2006 facilitated this transition by imposing stricter funding requirements on DB plans and enhancing the attractiveness of DC plans through various incentives (https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v69n3/v69n3p1.html).

Running parallel, the recent trend of labor unions—such as the massive United Auto Workers (UAW)—investing membership dues in the stock market, including in companies they might challenge or negotiate with, starkly illustrates how union bureaucracies are increasingly co-opted by the very corporate forces they are supposed to oppose. From the 1980s onward, the government-corporate alliance has evolved into a toxic web of aggressive market liberalization and ruthless deregulation. The calculated removal of oversight was a brazen move that handed corporations unchecked power while shredding public accountability. Worker protections were gutted, and investment returns soared on the backs of labor exploitation, as corporate greed flourished at the expense of those who toil.

The UAW, like many other unions, seized on the opportunity to increase their cash reserves and began channeling part of their dues and pension funds into the stock market. Superficially, this was a move to diversify and increase the assets available to serve and protect members. However, it effectively entangled the unions' financial interests with those of the very corporations they were meant to be monitoring and moderating, at the very least.

This alignment with corporate performance underscores a deeper ideological shift within the union bureaucracy, from champions of workers' rights to managers of complex financial portfolios. This shift has distanced the union's leadership from the everyday realities and immediate needs of their rank-and-file members, leading to decisions that favor long-term financial stability over aggressive advocacy for better wages, benefits, or working conditions.

In both scenarios, workers face a ridiculous contradiction: pursuing their true interest in collective emancipation from the exploitative capitalist class risks undermining their wages, benefits, and retirement savings.

The Paradox of Worker Investment in Corporate Profits

The transition from traditional pension plans to 401(k) plans encapsulates a critical transformation in the relationship between labor and capital, deeply embedded with ideological and material implications.

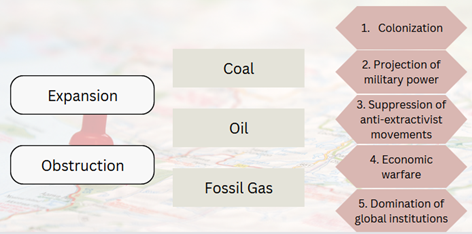

By investing their retirement savings in the stock market, workers are compelled to support, and indeed root for, the success of the very entities that exploit their labor. The corporate profits that boost their retirement funds are sourced directly from corporate strategies such as suppressing wages, reducing workforce sizes, and demanding increased productivity. This is effectively a transfer of wealth from workers to the rulers, who assume the title of “shareholders” and “executives.” Yet, this extraction of wealth is cleverly disguised as a harmless, or more often, benign, retirement savings scheme, misleading workers into passively acquiescing to their own exploitation.

Under the oppressive gears of capitalism, driven by the relentless hunger for perpetual growth, these savings plans don't just subtly coerce workers into endorsing their own exploitation—they force them to champion an ever-escalating cycle of exploitation. This vicious spiral is demanded by a system addicted to ceaseless profit increases year after year, chaining workers to a fate where they root for deeper cuts into their own flesh. Essentially, through these defined contribution plans, workers unwittingly empower their rulers to repeatedly enact the very cost-cutting measures that threaten their jobs, deny them raises, and increase their workload and hours.

Relinquishing Control

A troubling feature of 401(k) plans is the significant loss of control they impose on workers, who must hand over their financial decision-making to corporate giants like Vanguard, Blackrock, or State Street. Workers are compelled to hand over their retirement funds to corporations like Vanguard, Blackrock, or State Street because these financial goliaths contract with employers to manage 401(k) plans, effectively controlling the investment options and strategies available to employees. These management companies administer 401(k) plans, offering workers only a limited selection of investment options that are chosen to serve corporate goals rather than the financial needs or preferences of the employees themselves. This limited selection gives the appearance of choice, but in reality, it substantially diminishes workers' autonomy over their own retirement funds.

In other words, these managers make critical investment decisions without direct input from the workers, decisions that shape the potential growth and security of the workers' retirement savings. Consequently, workers are left on the sidelines, passive observers of their own financial destinies, reliant on the strategies and ethical considerations of entities that prioritize corporate profitability over individual security.

Despite the fact that, collectively, the controlling stake in almost all publicly traded companies is technically "owned" by a broad base of worker-investors, the reality is starkly different. By channeling investments through entities like Vanguard, workers are stripped of any direct influence over corporate actions. When workers entrust their savings to financial behemoths like Vanguard, they effectively hand over their shareholder "voting rights," surrendering any semblance of control over the corporations their collective labor has built.

This arrangement starkly illustrates how capitalist structures co-opt workers’ assets for corporate gain, rendering them powerless in decisions that affect their own economic futures. Intermediaries like Vanguard wield our collective power to relentlessly pursue corporate profit growth, endorsing actions that ruthlessly undermine our interests as workers. They push for job cuts, relentless lobbying against fair wage laws, and environmental shortcuts—all leveraging our collective votes to bolster shareholder value at the expense of the very workforce that enables it.

The systemic channeling of worker investments into entities like Vanguard, Blackrock, and State Street is not merely a feature of modern financial management; it is a cornerstone of capitalist power dynamics. This process ensures that the vast pool of capital derived from workers' savings is used not to empower those workers as shareholders, but rather to fortify the very structures that oppress them. With our collective investments holding controlling stakes in nearly all publicly traded companies, the corporate elite deliberately divert this immense power into their own hands to maintain dominance. They design this system to crush any potential worker resistance, ensuring their agendas remain unchallenged while deepening economic disparities that empower the elite at the expense of the working majority.

Blindness to Class Antagonisms

The financialization of workers' savings essentially turns their labor into a commodity. By reducing their economic agency to numbers in an investment portfolio, workers are disconnected from the real outcomes of their own economic contributions. As their hard-earned money is invested in large capitalist enterprises, it's managed under the guise of seeking growth and security. However, this management actually reinforces the power structures that limit workers' autonomy and freedom.

Investment funds serve as tools that embed workers deeper within the capitalist system, presenting their subordinate position as a necessary efficiency rather than exploitation. This makes the process seem like prudent financial management, but it's really about maintaining the status quo. This creates a cognitive and practical dissonance, where the worker’s financial planning for the future is tied up with strategies that undermine their present livelihood and working conditions.

As workers see their retirement savings—invested in volatile stock markets—potentially jeopardized by decisive labor actions, there arises a rational general reluctance to engage in or support extensive strikes or vigorous protests. This caution stems from the fear that disrupting the market, even temporarily, could diminish their financial security, despite the potential long-term benefits such actions could have on improving working conditions.

Without the backing of unorganized laborers whose retirement funds are entrenched in the stock market, organized labor faces a much tougher challenge in gaining public support for substantial changes that would shift power from the elite to the people. This dynamic introduces a significant delay in the class struggle, reducing the momentum for radical change. Thus, the capitalist class gains a buffer period to adjust and refine oppressive strategies, reinforcing the status quo and perpetuating the cycle of worker exploitation, all while maintaining a facade of empowering workers through financial participation.

The capitalist class exploits this lag, not only through overt repression but also through more subtle forms of coercion. By shaping norms and expectations—such as the prioritization of market stability over the improvement of labor conditions—they manipulate workers into accepting, and even defending, a system that fundamentally works against their interests. This ideological control helps sustain the status quo, continually diverting attention from the systemic exploitation that underpins the capitalist system and muffling the calls for transformative change that might otherwise resonate through the working class. This clever manipulation of worker priorities ensures that any potential disruptions to capitalist accumulation are blunted, securing ongoing dominance by the ruling elites.

The UAW’s Investment Strategy and Worker Conflict

Even within organized labor contexts such as unions, bureaucratic structures often paralyze workers into a passive acceptance of a system that purports to aid their financial well-being while subtly undermining their real interests, just as unorganized laborers, with their retirement funds tied to the stock market, passively support the corporate entities they should be challenging. In unions, this dynamic is replicated through bureaucratic controls that bind workers to the same detrimental financial entanglements, ensuring that even within organized frameworks, the mechanisms ostensibly designed to empower workers instead reinforce their submission to a system that undermines their genuine interests.

For example, the UAW bureaucratic apparatus derives a substantial portion of its revenue from indirect auto company subsidies and Wall Street investments. These funds have been used not just for operational costs but to swell the ranks of its high-paid staff and finance extravagant leadership conferences, from which the ordinary union member is conspicuously absent.

Dues from UAW members are funneled into various mutual funds and stocks globally, including stakes in companies whose workers are represented by the union. In essence, the auto workers' union is investing in the very companies they are negotiating with for better wages and conditions! Notably, the UAW also has investments in notorious hedge funds like Bardin Hill Investment Partners and Kohlberg Investors IX, firms infamous for harsh worker cuts, operating out of places like the Cayman Islands. Thus, the UAW is investing in both the employers that exploit their own members and in corporate entities that extract wealth from workers generally.

As a result, net spending for the UAW, excluding strike payouts, escalated dramatically from $258 million in 2022 to $318.4 million in 2023, with compensation for headquarters staff rising from $52.57 million to nearly $59 million. This investment strategy has undeniably benefitted from the stock market's recent boom, driven largely by Wall Street's aggressive undermining of the working class's social standing, particularly through widespread layoffs, wage suppression, and the denial or reduction of benefits.

Ostensibly, these vast reserves bolster the UAW's strike fund, yet strikes are rarely called and are often restricted in scope. Last year's "stand up strike" saw most auto workers continue to labor, while the employers’ revenues actually increased. The strike fund, rather than serving as a militant tool against corporate power, increasingly appears as a financial cushion for the union bureaucratic elite, not the workers it claims to represent.

This arrangement embodies a conflict: while the union fights for better wages and conditions, its financial health and the ability of its strike fund to grow are largely dependent on the prosperity of the same corporate entities they may be contesting. This interdependence complicates the union’s role and its strategies in advocating for workers' rights.

Conflict Between Worker Advocacy and Financial Interests

The financial maneuvers of the UAW, particularly its investments in the very companies its members labor under, reveal a stark betrayal orchestrated by union elites. These leaders—career unionists who have risen through the ranks—are entrenched in safeguarding their own positions, power, and privileges at the expense of the rank-and-file workers they claim to represent. These bureaucratic elites have distanced themselves from the daily struggles of the workforce, becoming gatekeepers who often suppress radical initiatives that could genuinely empower workers.

This leadership stratum, with its grip firmly on the union’s strategic levers, has consistently shunned aggressive labor actions that might jeopardize their investment portfolios and their cozy relationships with corporate powerhouses, or possibly even invite state backlash. Their risk-averse, conservative tactics dilute the potential for revolutionary changes, favoring instead incrementalistic policies that do little more than maintain the status quo. In negotiations, these leaders are quick to prioritize job security over substantial wage increases or essential adaptations to industry evolution, such as retraining for emerging technologies. This strategy goes beyond mere conservatism; it is actively complicit. It represents a deliberate choice by a self-interested bureaucratic elite to align with corporations and a co-opted state, entities that actively resist transformative changes.

Reflection

The seismic shift from defined benefit (DB) plans to defined contribution (DC) plans marks a significant transformation in the landscape of worker retirement security. This transition encapsulates a broader trend in the neoliberal economic agenda, prioritizing market solutions and individual responsibility over collective welfare and guaranteed benefits. By shifting the burden of retirement savings to individuals, workers find themselves compelled to invest in and support the very corporate systems that may undermine their job security and wage growth. The involvement of financial giants like Vanguard in managing these investments exemplifies a deep entrenchment of capitalist interests in workers' lives. These firms, by controlling vast pools of retirement funds, not only influence corporate governance but also align workers' financial futures with the health of the stock market and corporate profitability, effectively muting potential collective dissent against exploitative practices.

In parallel, the role of unions like the UAW in this financialized landscape reveals a troubling convergence of interests between union leadership and corporate power. As unions invest in the stock market, including in companies they negotiate with, there arises a conflict between advocating for robust labor rights and maintaining the financial performance of their investments. This duality suggests a corrosion of union solidarity, driven by a bureaucratic elite more attuned to the fluctuations of the market than to the struggles of the rank-and-file members. Such dynamics underscore a broader erosion of labor power, where the traditional role of unions as bulwarks against corporate excess is compromised, making them less a force for challenging the status quo and more a part of the financial systems they should be critiquing.

It's time to disengage from these capitalist structures that exploit us and instead cultivate solidarity rooted in class consciousness. Only by recognizing our collective power and prioritizing mutual welfare can we dismantle the financial machinery that subjugates workers and reclaim our future.

Peter S. Baron is the author of “If Only We Knew: How Ignorance Creates and Amplifies the Greatest Risks Facing Society” (https://www.ifonlyweknewbook.com) and is currently pursuing a J.D. and M.A. in Philosophy at Georgetown University.