By Alan Macleod

Republished from Mint Press News.

“A Black uprising is shaking Cuba’s Communist regime,” read The Washington Post ’sheadline on the recent unrest on the Caribbean island. “Afro-Cubans Come Out In Droves To Protest Government,” wrote NPR .Meanwhile, The Wall Street Journal went with “Cuba’s Black Communities Bear the Brunt of Regime’s Crackdown” as a title.

These were examples of a slew of coverage in the nation’s top outlets, which presented what amounted to one day of U.S.-backed protests in July as a nationwide insurrection led by the country’s Black population — in effect, Cuba’s Black Lives Matter moment.

Apart from dramatically playing up the size and scope of the demonstrations, the coverage tended to rely on Cuban emigres or other similarly biased sources. One noteworthy example of this was Slate ,which interviewed a political exile turned Ivy League professor presenting herself as a spokesperson for young Black working class Cubans. Professor Amalia Dache explicitly linked the struggles of people in Ferguson, Missouri with that of Black Cuban groups. “We’re silenced and we’re erased on both fronts, in Cuba and the United States, across racial lines, across political lines,” she said.

Dache’s academic work — including “Rise Up! Activism as Education” and “Ferguson’s Black radical imagination and the cyborgs of community-student resistance,” — shows how seemingly radical academic work can be made to dovetail with naked U.S. imperialism. From her social media postings ,Dache appears to believe there is an impending genocide in Cuba. Slate even had the gall to title the article “Fear of a Black Cuban Planet” — a reference to the militant hip-hop band Public Enemy, even though its leader, Chuck D, has made many statements critical of U.S. intervention in Cuba.

Perhaps more worryingly, the line of selling a U.S.-backed color revolution as a progressive event even permeated more radical leftist publications. NACLA — the North American Congress on Latin America, an academic journal dedicated, in its own words, to ensuring “the nations and peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean are free from oppression and injustice, and enjoy a relationship with the United States based on mutual respect, free from economic and political subordination” — published a number of highly questionable articles on the subject.

One, written by Bryan Campbell Romero, was entitled “Have You Heard, Comrade? The Socialist Revolution Is Racist Too,” and described the protests as “the anger, legitimate dissatisfaction, and cry for freedom of many in Cuba,” against a “racist and homophobic” government that is unquestionably “the most conservative force in Cuban society.”

Campbell Romero described the government’s response as a “ruthless … crackdown” that “displayed an uncommon disdain for life on July 11.” The only evidence he gave for what he termed “brutal repression” was a link to a Miami-based CBS affiliate, which merely stated that, “Cuban police forcibly detained dozens of protesters. Video captured police beating demonstrators,” although, again, it did not provide evidence for this.

Campbell Romero excoriated American racial justice organizations like Black Lives Matter and The Black Alliance for Peace that sympathized with the Cuban government, demanding they support “the people in Cuba who are fighting for the same things they’re fighting for in the United States.”

“Those of us who are the oppressed working-class in the actual Global South — colonized people building the socialist project that others like to brag about — feel lonely when our natural allies prioritize domestic political fights instead of showing basic moral support,” he added. Campbell Romero is a market research and risk analyst who works for The Economist. Moreover, this oppressed working class Cuban proudly notes that his career development has been financially sponsored by the U.S. State Department.

Cuban government critic Bryan Campbell Romero proudly touts his US State Department-funded education

Unfortunately, the blatant gaslighting of U.S. progressives did not end there. The journal also translated and printed the essay of an academic living in Mexico that lamented that the all-powerful “Cuban media machine” had contributed to “the Left’s ongoing voluntary blindness.” Lionizing U.S.-funded groups like the San Isidro movement and explicitly downplaying the U.S. blockade, the author again appointed herself a spokesperson for her island, noting “we, as Cubans” are ruled over by a “military bourgeoisie” that has “criminaliz[ed] dissent.” Such radical, even Marxist rhetoric is odd for someone who is perhaps best known for their role as a consultant to a Danish school for entrepreneurship.

NACLA’s reporting received harsh criticism from some. “This absurd propaganda at coup-supporting website NACLA shows how imperialists cynically weaponize identity politics against the left,” reacted Nicaragua-based journalist Ben Norton .“This anti-Cuba disinfo was written by a right-wing corporate consultant who does ‘market research’ for corporations and was cultivated by U.S. NGOs,” he continued, noting the journal’s less than stellar record of opposing recent coups and American regime change operations in the region. In fairness to NACLA, it also published far more nuanced opinions on Cuba — including some that openly criticized previous articles — and has a long track record of publishing valuable research.

“The radlib academics at @NACLA supported the violent US-backed right-wing coup attempt in Nicaragua in 2018, numerous US coup attempts in Venezuela, and now a US regime-change operation in Cuba.

NACLA is basically an arm of the US State Department https://t.co/xxFvxMemxo”

— Ben Norton (@BenjaminNorton) August 12, 2021

BLM Refuses to Play Ball

The framing of the protests as a Black uprising against a conservative, authoritarian, racist government was dealt a serious blow by Black Lives Matter itself, which quickly released a statement in solidarity with Cuba, presenting the demonstrations as a consequence of U.S. aggression. As the organization wrote:

The people of Cuba are being punished by the U.S. government because the country has maintained its commitment to sovereignty and self-determination. United States leaders have tried to crush this Revolution for decades.

Such a big and important organization coming out in unqualified defense of the Cuban government seriously undermined the case that was being whipped up, and the fact that Black Lives Matter would not toe Washington’s line sparked outrage among the U.S. elite, leading to a storm of condemnation in corporate media. “Cubans can’t breathe either. Black Cuban lives also matter; the freedom of all Cubans should matter,” The Atlantic seethed. Meanwhile, Fox News contributor and former speechwriter for George W. Bush, Marc A. Thiessen claimed in The Washington Post that “Black Lives Matter is supporting the exploitation of Cuban workers” by supporting a “brutal regime” that enslaves its population, repeating the dubious Trump administration claim that Cuban doctors who travel the world are actually slaves being trafficked.

Despite the gaslighting, BLM stood firm, and other Black organizations joined them, effectively ending any hopes for a credible shot at intersectional imperialist intervention. “The moral hypocrisy and historic myopia of U.S. liberals and conservatives, who have unfairly attacked BLM’s statement on Cuba, is breathtaking,” read a statement from the Black Alliance for Peace.

Trying to Create a Cuban BLM

What none of the articles lauding the anti-government Afro-Cubans mention is that for decades the U.S. government has been actively stoking racial resentment on the island, pouring tens of millions of dollars into astroturfed organizations promoting regime change under the banner of racial justice.

Reading through the grants databases for Cuba from U.S. government organizations like the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and USAID, it immediately becomes clear that Washington has for years chosen to target young people, particularly Afro-Cubans, and exploit real racial inequalities on the island, turning them into a wedge issue to spark unrest, and, ultimately, an insurrection.

For instance, a 2020 NED project, entitled “Promoting Inclusion of Marginalized Populations in Cuba,” notes that the U.S. is attempting to “strengthen a network of on-island partners” and help them to interact and organize with one another.

A second mission, this time from 2016, was called “promoting racial integration.” But even from the short blurb publicly advertising what it was doing, it is clear that the intent was the opposite. The NED sought to “promote greater discussion about the challenges minorities face in Cuba,” and publish media about the issues affecting youth, Afro-Cubans and the LGBTI community in an attempt to foster unrest.

A 2016 NED grant targets hides hawkish US policy goals behind altruistic language like “promoting racial integration”

Meanwhile, at the time of the protests, USAID was offering $2 million worth of funding to organizations that could “strengthen and facilitate the creation of issue-based and cross-sectoral networks to support marginalized and vulnerable populations, including but not limited to youth, women, LGBTQI+, religious leaders, artists, musicians, and individuals of Afro-Cuban descent.” The document proudly asserts that the United States stands with “Afro-Cubans demand[ing] better living conditions in their communities,” and makes clear it sees their future as one without a Communist government.

The document also explicitly references the song “Patria y Vida,” by the San Isidro movement and Cuban emigre rapper Yotuel, as a touchstone it would like to see more of. Although the U.S. never discloses who exactly it is funding and what they are doing with the money, it seems extremely likely that San Isidro and Yotuel are on their payroll.

“Such an interesting look at the new generation of young people in #Cuba & how they are pushing back against govt repression. A group of artists channeled their frustrations into a wildly popular new song that the government is now desperate to suppress.” https://t.co/47RGc9ORuR

— Samantha Power (@SamanthaJPower) February 24, 2021

Only days after “Patria y Vida” was released, there appeared to be a concerted effort among high American officials to promote the track, with powerful figures such as head of USAID Samantha Power sharing it on social media. Yotuel participates in public Zoom calls with U.S. government officials while San Isidro members fly into Washington to glad-hand with senior politicians or pose for photos with American marines inside the U.S. Embassy in Havana. One San Isidro member said he would “give [his] life for Trump” and beseeched him to tighten the blockade of his island, an illegal action that has already cost Cuba well over $1 trillion, according to the United Nations. Almost immediately after the protests began, San Isidro and Yotuel appointed themselves leaders of the demonstrations, the latter heading a large sympathy demonstration in Miami.

“The whole point of the San Isidro movement and the artists around it is to reframe those protests as a cry for freedom and to make inroads into progressive circles in the U.S.,” said Max Blumenthal, a journalist who has investigated the group’s background.

Rap As A Weapon

From its origins in the 1970s, hip hop was always a political medium. Early acts like Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation, KRS One, and Public Enemy spoke about the effect of drugs on Black communities, police violence, and building movements to challenge power.

By the late 1990s, hip hop as an art form was gaining traction in Cuba as well, as local Black artists helped bring to the fore many previously under-discussed topics, such as structural racism.

Afro-Cubans certainly are at a financial disadvantage. Because the large majority of Cubans who have left the island are white, those receiving hard currency in the form of remittances are also white, meaning that they enjoy far greater purchasing power. Afro-Cubans are also often overlooked for jobs in the lucrative tourism industry, as there is a belief that foreigners prefer to interact with those with lighter skin. This means that their access to foreign currency in the cash-poor Caribbean nation is severely hampered. Blacks are also underrepresented in influential positions in business or education and more likely to be unemployed than their white counterparts. In recent times, the government has tried to take an activist position, passing a number of anti-racism laws. Nevertheless, common attitudes about what constitutes beauty and inter-racial relationships prove that the society is far from a racially egalitarian one where Black people face little or no discrimination.

The new blockade on remittances, married with the pandemic-induced crash in tourism, has hit the local economy extremely hard, with unemployment especially high and new shortages of some basic goods. Thus, it is certainly plausible that the nationwide demonstrations that started in a small town on the west side of the island were entirely organic to begin with. However, they were also unquestionably signal-boosted by Cuban expats, celebrities and politicians in the United States, who all encouraged people out on the streets, insisting that they enjoyed the full support of the world’s only superpower.

However, it should be remembered that Cuba as a nation was crucial in bringing about the end of apartheid in South Africa, sending tens of thousands of troops to Africa to defeat the racist apartheid forces, a move that spelled the end for the system. To the last day, the U.S. government backed the white government.

Washington saw local rappers’ biting critiques of inequality as a wedge issue they could exploit, and attempted to recruit them into their ranks, although it is far from clear how far they got in this endeavor, as their idea of change rarely aligned with what rappers wanted for their country.

Sujatha Fernandes, a sociologist at the University of Sydney and an expert in Cuban hip hop told MintPress:

"For many years, under the banner of regime change, organizations like USAID have tried to infiltrate Cuban rap groups and fund covert operations to provoke youth protests. These programs have involved a frightening level of manipulation of Cuban artists, have put Cubans at risk, and threatened a closure of the critical spaces of artistic dialogue many worked hard to build.”

In 2009, the U.S. government paid for a project whereby it sent music promoter and color-revolution expert Rajko Bozic to the island. Bozic set about establishing contacts with local rappers, attempting to bribe them into joining his project. The Serbian found a handful of artists willing to participate in the project and immediately began aggressively promoting them, using his employers’ influence to get their music played on radio stations. He also paid big Latino music stars to allow the rappers to open up for them at their gigs, thus buying them extra credibility and exposure. The project only ended after it was uncovered, leading to a USAID official being caught and jailed inside Cuba.

Despite the bad publicity and many missteps, U.S. infiltration of Cuban hip hop continues to this day. A 2020 NED project entitled “Empowering Cuban Hip-Hop Artists as Leaders in Society” states that its goal is to “promote citizen participation and social change” and to “raise awareness about the role hip-hop artists have in strengthening democracy in the region.” Many more target the wider artistic community. For instance, a recent scheme called “Promoting Freedom of Expression of Cuba’s Independent Artists” claimed that it was “empower[ing] independent Cuban artists to promote democratic values.”

Of course, for the U.S. government, “democracy” in Cuba is synonymous with regime change. The latest House Appropriations Bill allocates $20 million to the island, but explicitly stipulates that “none of the funds made available under such paragraph may be used for assistance for the Government of Cuba.” The U.S. Agency for Global Media has also allotted between $20 and $25 million for media projects this year targeting Cubans.

BLM For Me, Not For Thee

What is especially ironic about the situation is that many of the same organizations promoting the protests in Cuba as a grassroots expression of discontent displayed a profound hostility towards the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, attempting to defame genuine racial justice activists as pawns of a foreign power, namely the Kremlin.

In 2017, for example, CNN released a story claiming that Russia had bought Facebook ads targeting Ferguson and Baltimore, insinuating that the uproar over police murders of Black men was largely fueled by Moscow, and was not a genuine expression of anger. NPR-affiliate WABE smeared black activist Anoa Changa for merely appearing on a Russian-owned radio station. Even Vice President Kamala Harris suggested that the hullabaloo around Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protest was largely cooked up in foreign lands.

Meanwhile, at the height of the George Floyd protests in 2020, The New York Times asked Republican Senator Tom Cotton to write an op-ed called “Send in the Troops,” in which he asserted that “an overwhelming show of force” was necessary to quell “anarchy” from “criminal elements” on our streets.

Going further back, Black leaders of the Civil Rights era, such as Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King, were continually painted as in bed with Russia, in an attempt to delegitimize their movements. In 1961, Alabama Attorney General MacDonald Gallion said ,“It’s the communists who were behind this integration mess.” During his life, Dr. King was constantly challenged on the idea that his movement was little more than a communist Trojan Horse. On Meet the Press in 1965, for instance, he was asked whether “moderate Negro leaders have feared to point out the degree of communist infiltration in the Civil Rights movement.”

Nicaragua

The U.S. has also been attempting to heighten tensions between the government of Nicaragua and the large population of Miskito people who live primarily on the country’s Atlantic coast. In the 1980s, the U.S. recruited the indigenous group to help in its dirty war against the Sandinistas, who returned to power in 2006. In 2018, the U.S. government designated Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela as belonging to a “troika of tyranny” — a clear reference to the second Bush administration’s Axis of Evil pronouncement.

Washington has both stoked and exaggerated tensions between the Sandinistas and the Miskito, its agencies helping to create a phony hysteria over supposed “conflict beef” — a scandal that seriously hurt the Nicaraguan economy.

The NED and USAID have been active in Nicaragua as well, attempting to animate racial tensions in the Central American nation. For instance, a recent 2020 NED project ,entitled “Defending the Human Rights of Marginalized Communities in Nicaragua,” claims to work with oppressed groups (i.e., the Miskito), attempting to build up “independent media” to highlight human rights violations.

To further understand this phenomenon, MintPress spoke to John Perry, a journalist based in Nicaragua. “What is perhaps unclear is the extent to which the U.S. has been engaged,” he said, continuing:

"There is definitely some engagement because they have funded some of the so-called human rights bodies that exist on the Atlantic coast [where the Miskito live]. Basically, they — the U.S.-funded NGOs — are trying to foment this idea that the indigenous communities in the Atlantic coast are subjected to genocide, which is completely absurd.”

In 2018, the U.S. backed a wave of violent demonstrations across the country aimed at dislodging the Sandinistas from power. The leadership of the Central American color revolution attempted to mobilize the population around any issue they could, including race and gender rights. However, they were hamstrung from the start, as Perry noted:

"The problem the opposition had was that it mobilized young people who had been trained by these U.S.-backed NGOs and they then enrolled younger people disenchanted with the government more generally. To some extent they mobilized on gay rights issues, even though these are not contentious in Nicaragua. But they were compromised because one of their main allies, indeed, one of the main leaders of the opposition movement was the Catholic Church, which is very traditional here.”

U.S. agencies are relatively open that their goal is regime change. NED grants handed out in 2020 discuss the need to “promote greater freedom of expression and strategic thinking and analysis about Nicaragua’s prospects for a democratic transition” and to “strengthen the capacity of pro-democracy players to advocate more effectively for a democratic transition” under the guise of “greater promot[ion of] inclusion and representation” and “strengthen[ing] coordination and dialogue amongst different pro-democracy groups.” Meanwhile, USAID projects are aimed at getting “humanitarian assistance to victims of political repression,” and “provid[ing] institutional support to Nicaraguan groups in exile to strengthen their pro-democracy efforts.” That polls show a large majority of the country supporting the Sandinista government, which is on course for a historic landslide in the November election, does not appear to dampen American convictions that they are on the side of democracy. Perry estimates that the U.S. has trained over 8,000 Nicaraguans in projects designed to ultimately overthrow the Sandinistas.

In Bolivia and Venezuela, however, the U.S. government has opted for exactly the opposite technique; backing the country’s traditional white elite. In both countries, the ruling socialist parties are so associated with their indigenous and/or Black populations and the conservative elite with white nationalism that Washington has apparently deemed the project doomed from the start.

China

Stoking racial and ethnic tension appears to be a ubiquitous U.S. tactic in enemy nations. In China, the Free Tibet movement is being kept alive with a flood of American cash. There have been 66 large NED grants to Tibetan organizations since 2016 alone. The project titles and summaries bear a distinct similarity to Cuban and Nicaraguan undertakings, highlighting the need to train a new generation of leaders to participate in society and bring the country towards a democratic transition, which would necessarily mean a loss of Chinese sovereignty.

Likewise, the NED and other organizations have been pouring money into Hong Kong separatist groups (generally described in corporate media as “pro-democracy activists”). This money encourages tensions between Hong Kongers and mainland Chinese with the goal of weakening Beijing’s influence in Asia and around the world. The NED has also been sending millions to Uyghur nationalist groups.

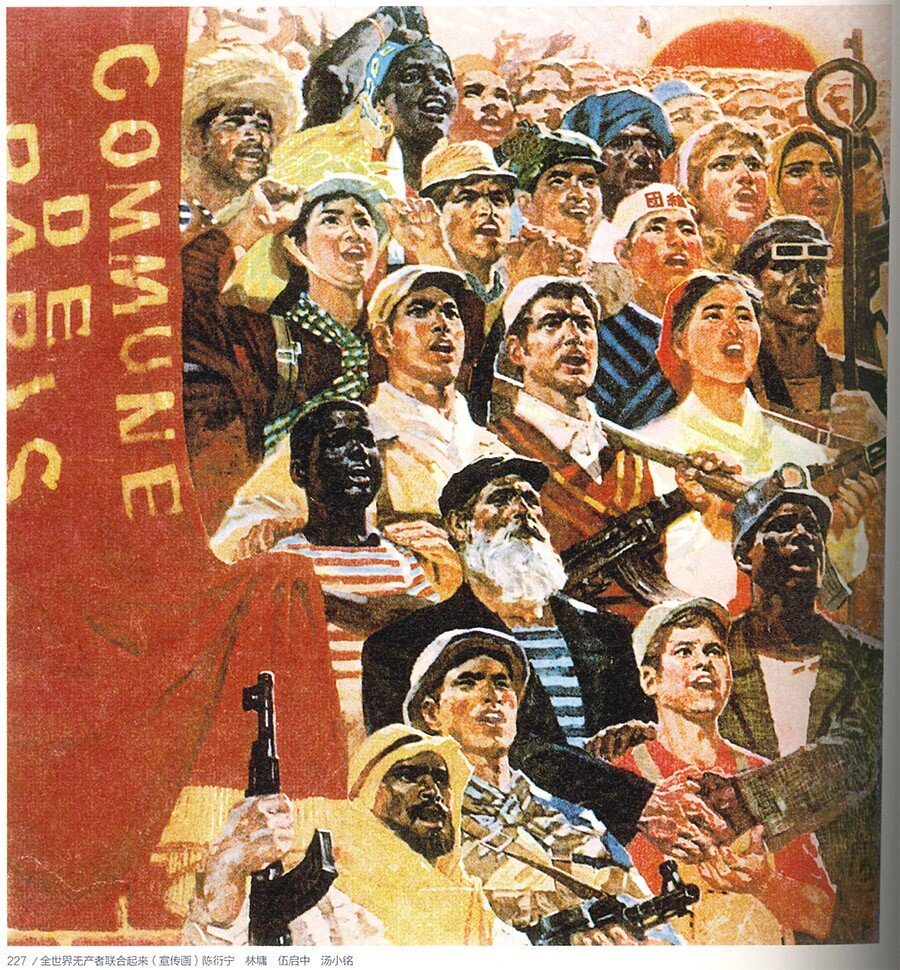

Intersectional Empire

In Washington’s eyes, the point of funding Black, indigenous, LGBT or other minority groups in enemy countries is not simply to promote tensions there; it is also to create a narrative that will be more likely to convince liberals and leftists in the United States to support American intervention.

Some degree of buy-in, or at least silence, is needed from America’s more anti-war half in order to make things run smoothly. Framing interventions as wars for women’s rights and coup attempts as minority-led protests has this effect. This new intersectional imperialism attempts to manufacture consent for regime change, war or sanctions on foreign countries among progressive audiences who would normally be skeptical of such practices. This is done through adopting the language of liberation and identity politics as window dressing for domestic audiences, although the actual objectives — naked imperialism — remain the same as they ever were.

The irony is that the U.S. government is skeptical, if not openly hostile, to Black liberation at home. The Trump administration made no effort to disguise its opposition to Black Lives Matter and the unprecedented wave of protests in 2020. But the Biden administration’s position is not altogether dissimilar, offering symbolic reforms only. Biden himself merely suggested that police officers shoot their victims in the leg, rather than in the chest.

Thus, the policy of promoting minority rights in enemy countries appears to be little more than a case of “Black Lives Matter for thee, but not for me.” Nonetheless, Cuba, Nicaragua, China and the other targets of this propaganda will have to do more to address their very real problems on these issues in order to dilute the effectiveness of such U.S. attacks.

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.